Blog

Latest Posts

-

The Sidewalk Salsa and Cultural Sensitivities

Walking along a city sidewalk or heading down a narrow hallway, not one of us has avoided doing that little dance at least once. Living in large cities, and even occasionally leaving my apartment for a few minutes each week, I’ve done the Sidewalk Salsa a thousand times.

You twist to the right, but they mirror you. You twist back even further to the left, and they’ve already tried to correct their ill move. Or perhaps you’re the inadvertent aggressor in this ambulation incursion. Now you’re both locked in a battle of wills, ego, and agility of the hip flexors to see who forces a weak laugh first and, stopped in place with palms turned up, yields the entire avenue through a gentle swing of their arms and a slight nod of the head. Or perhaps one side believes defusing the tension and mutual embarrassment requires play as a linebacker[1], only prolonging the interruption of travel for everyone involved.

Or so it frequently happens when the crowds are thin and at least one party isn’t racing to their destination. When time is short, and moods moreso, the salsa can quickly become a skirmish. Mettle replaced by brute physicality, and then the shoving begins. But most people aren’t seeking out conflict, and thus ends the intro to this post.[2]

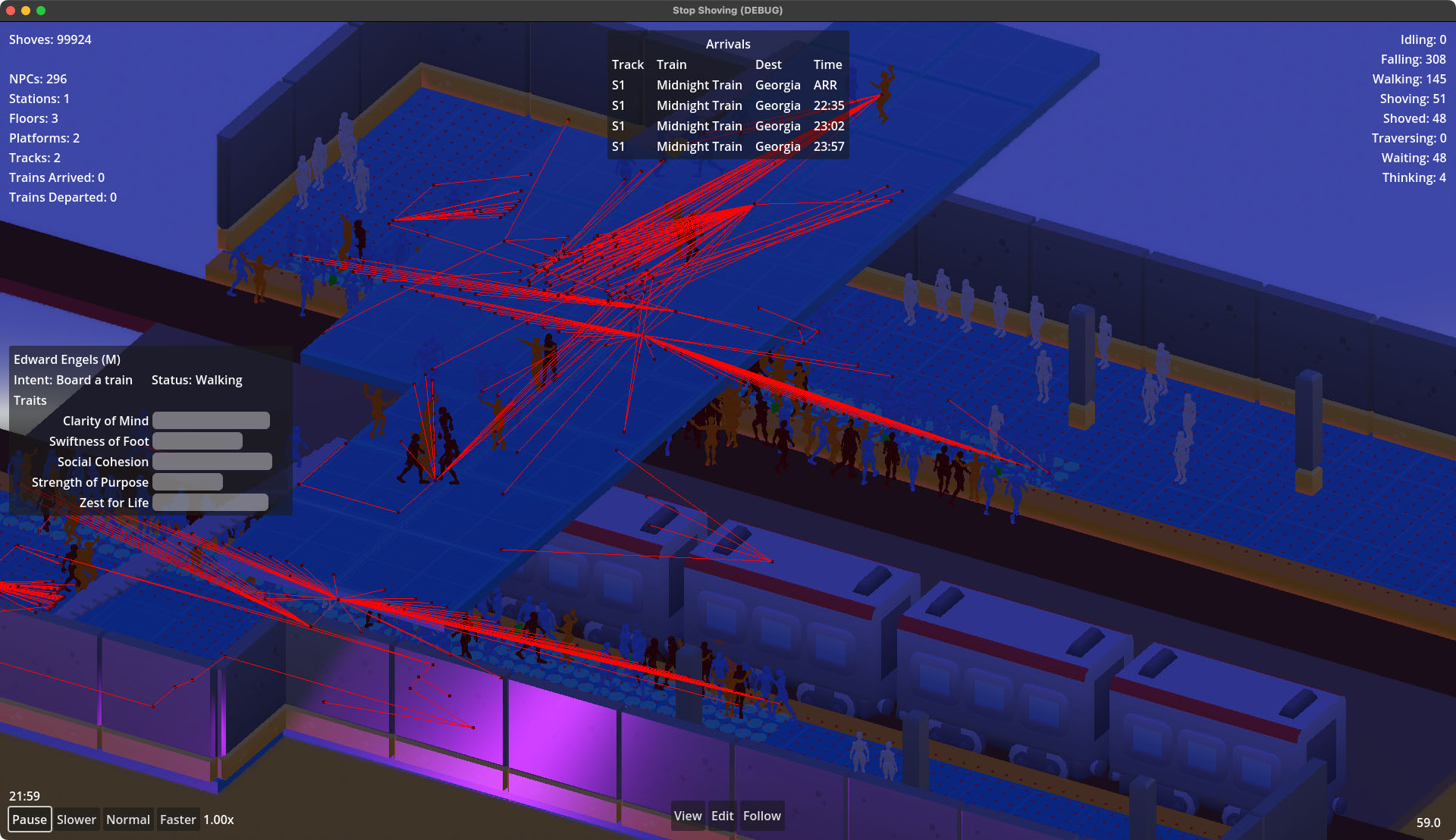

How to capture these kinds of interactions in a crowd simulation within the confined spaces of mass transit stations? How to get two or more NPCs on a collision course to try to avoid each other, but do it awkwardly and leave open the chance that one of those NPCs is just a big ol’ jerk? Most importantly, how to do it all while respecting cultural norms around the world?

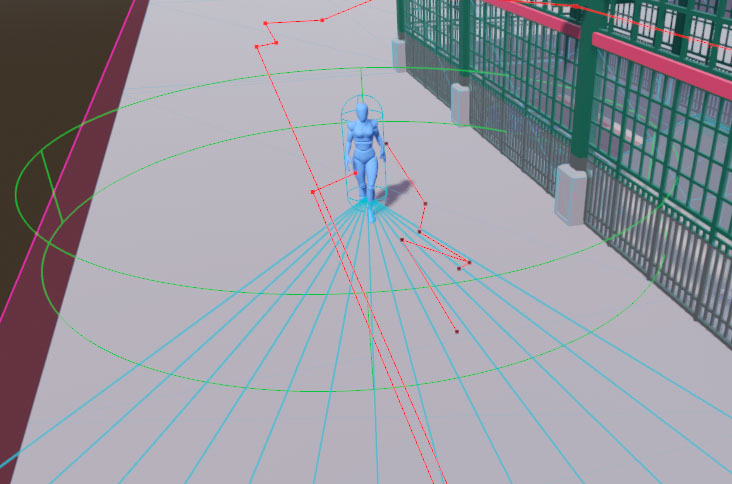

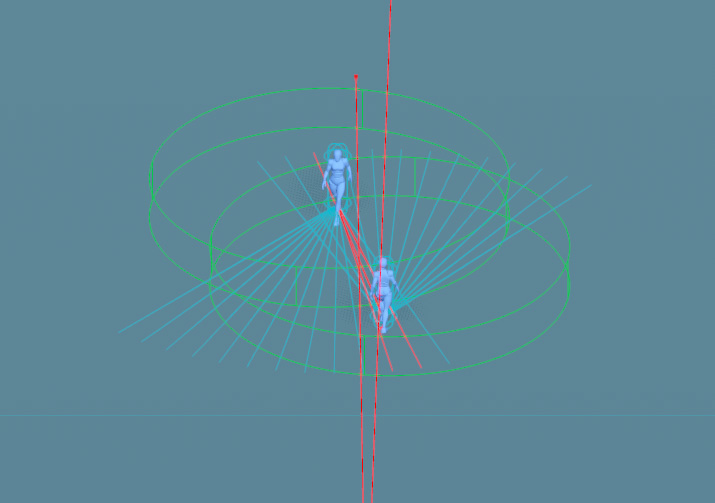

The core of Stop Shoving!'s approach[3] begins with an arc of

RayCast3Ds projected in front of every navigating NPC. Each has its origin at the same point just very slightly in front of the NPC and their rotations are made at even intervals such that their target points form an arc some distance ahead of the NPC. This configuration can be trivially tailored to each NPC to give more individualized behaviors (more situationally aware NPCs can have a larger arc, more myopic NPCs a narrower one; more nimble NPCs can have more rays, less agile and responsive NPCs fewer) using just a few variables:@export var num_rays : int = 13: set(n): num_rays = clamp(n + (n % 2) - 1, 3, 21) @export var ray_arc : float = 60 @export var ray_len : float = 7.5 @export var ray_cluster_margin : int = 2We’ll come back to the

ray_cluster_marginin a bit. Aside from explaining thatray_arcis the total rotation (in degrees, not radians) to be made from the right-most ray to the left-most ray, and thatray_lenis the length of each ray (in meters), the first important thing to point out is that the number of rays each NPC uses must be odd, as we will always want one ray to act as the dead-ahead center ray in this scheme. The custom setter on thenum_raysvariable ensures this,[4] as it also ensures that there will always be at least 3 rays and no more than 21.The maximum number is arbitrary and is there to prevent an NPC from bringing down armageddon on the physics thread. The defaults in this snippet are what I’ve been using most recently for testing the simulation, but they’re by no means some set of magic numbers that has perfectly captured real world human behavior. They do a pretty good job for the purposes of the game as-it-is so far, though.

With those values set, it’s possible to construct an array of rays, fanning out from the NPC. With a few pieces removed for brevity, it looks like this:

var arc_start : float = (ray_arc / 2) * -1 var arc_incr : float = ray_arc / (num_rays - 1) var rays : Array[RayCast3D] = [] for i : int in num_rays: var ray_rot : float = arc_start + (arc_incr * i) var ray = RayCast3D.new() ray.target_position = Vector3(0,0,ray_len) ray.rotate(Vector3.UP, deg_to_rad(ray_rot)) rays.push_back(ray)The full implementation adds each ray to a

Node3Dunderneath the NPC’s root so that it’s active within the physics engine, and for convenience it’s that node which is offset just a smidge in front of the NPC so the individual rays don’t need to worry about it. I’ve cut that out so this example focuses just on getting the rays created and pointed to the correct spots. Also, if you want to build a similar setup in an engine other than Godot, take care to remember that while Godot uses a Y-up-right-handed 3D space, not all engines do. A Z-up engine would require adjusting the vector assignment for the length to use the correct X or Y axis depending on your NPC orientation, and a left-handed engine would requirearc_start = (ray_arc / 2)as well asray_rot = arc_start + (arc_incr * i * -1)to have everything else in this post work as intended.This gives us an array of rays where (n-1)/2 will fan left from the NPC’s forward position and the other (n-1)/2 fan out to the right, and a single ray will stick out directly in front with no rotation at all. A larger

num_rayspacks them in tighter for more fine-grained detection and avoidance, and a higherray_arcallows the NPC to consider a larger area when trying to avoid another NPC.How do we use this array of rays, then, to have NPCs move around each other? Glad you asked, maybe I’ll write up a blog post on it! In the meantime, here’s how we use them: a combination of clusters and biases. Good biases, not the nasty, evil, all too pervasive ones that cause us to not love one another as sisters and brothers.

In some countries, everyone drives on the right, others the left. (In a few it’s both, depending on the region and its colonial history.) In most, walking patterns match. Oblivious tourists shoulder-checking locals, not just because it may be crowded, but because they aren’t picking up on the cue that nearly everyone around them is walking and yielding to the left while they barrel their way down the sidewalk on the right like they do back home. We can encode this in a regional setting that station scenes use: a bias which is going to give us an easy way to enforce[5] this right vs. left handedness in societal and cultural norms, and oh-so-conveniently it will also give us a way to get NPCs to do those awkward little dances.

func get_directional_bias() -> int:I’m going to be real hand-wavy about this part, because what that

SSG_NPCinstance method does internally is very specific to how Stop Shoving! works; checking for the station’s regional setting, potentially modifying it for the NPC’s attributes around social cohesion, confusion, and so on. The only important part is that the method ultimately returns an integer, either-1(to signify right) or1(to signify left), and nothing else. This method is also only called infrequently and it only produces a new and potentially different value at various frame intervals (i.e. you could call it repeatedly in the same frame and you’ll get back the same result, but call it again, say 12 frames, later and it might change its mind). It isn’t something that’s queried throughout the collision checks, but rather a one time pre-avoidance-routine setup call. With that all poorly explained, tuck the notion of the bias away for a moment.

Earlier I promised we’d get to that

ray_cluster_marginexport variable, and now that now isn’t earlier, let’s consider doing so. We built an array of rays above, but when checking for impending collisions (and looking for places to nudge the NPC where there won’t be any) we aren’t going to consider just one at a time. If an NPC is about to run into something, we need to find a direction they can turn to which has a high likelihood of not encountering something else to hit.A

RayCast3Dis, despite its name, actually a one-dimensional construct; it’s just one that you can use inside a 3D space (as opposed to theRayCast2Dwhich is also a one-dimensional construct, but one that works in 2D space). It is a single point projected along a single axis, and thus can only detect a collision in a very small area; much smaller than an NPC. This feature makes them very cheap (relatively speaking) to use but can easily lead to a scenario where the ray just happens to find a sliver of space right in between two other objects that narrowly misses them both for a point in space, but produces an angle from the NPC which would still cause collisions for the character’s body.There are other ways of checking for collisions in Godot, as in any other engine. We could use an array of neighboring or overlapping

Area3Ds, each a pizza slice of the semi-circle ahead of the NPC. That would give us effectively perfect detection of non-colliding areas the NPC could turn towards if the one in front of them has any NPCs. But we’d need several, and Area3Ds, especially non-primitive (cube, sphere, cylinder) shapes, are very expensive. We’d hit the physics engine’s limits quickly and our stations would only be able to contain a few dozen NPCs or less before the framerate collapses.We could try to optimize physics performance by only persisting the center one during navigation and dynamically creating the others only as-needed, but then we just move a lot of load over to the main thread and we introduce latency in between detecting a forward collision and being able to start scanning for non-colliding alternatives. The collision detection on each of the new areas dynamically generated wouldn’t be available until at least the frame after the one in which they were added.

Another option would be to use

ShapeCast3D. These are similar in concept to theRayCast3Din that you have an origin point and a target, and anything between the two will collide. The difference is that the ray cast projects a single point along that axis, whereas the shape cast moves an entire and arbitraryCollisionShape3Dalong it which can be used to cover whatever size area you desire. As with using Area3Ds, this is substantially more compute intensive than a raycast, but it can be implemented more efficiently than a series of fixed areas and in a way that reduces latency if performing the shapecast sweep directly against the physics server.In a simulation that either has a defined upper limit of NPCs to consider[6] or doesn’t need to maintain high framerates in realtime, shapecasting would be my preferred solution. One shapecast per NPC persists at all times while the NPC navigates, projected forward, with a lateral dimension equivalent to the NPC’s collision size. Upon registering a collision, the point of that collision in global space could be used to then shapecast almost-perpendicularly in the direction of the bias until a segment large enough to accommodate the original NPC is found. That area then defines the new safe trajectory of the NPC. Repeat those checks ad nauseum while the NPC is moving about and until you sprinkle in a little human-like variance, you’ve got a nearly perfect little avoidance system.

But that’s all still very expensive as you start piling on the NPCs. So performance constraints demand that we work with the humble raycasts, which is fine because video games are nothing if not smoke and mirrors. It just has to be good enough while remaining fast.

To compromise, we’ll bundle up those raycasts into overlapping clusters, and set a rule that if any one ray in a given cluster is colliding then we treat that entire cluster as colliding. This is going to let us fake more than one dimension of coverage. And for the third time I will call out

ray_cluster_marginand this time I’ll actually explain what it is: the number of rays to each side of whatever ray we’re currently dealing with that will be considered members of the cluster. A margin of 1 means the clusters will be 3 rays (the current ray, plus one to each side). Just as with the entire set of rays, the clusters will always have an odd number of rays within them so that we have, at all times, a center ray to deal with.It’s been a while since some code, so let’s see what the cluster-based ray scanning looks like with all the above in mind. I’m going to break the scanning method up into three parts, beginning with this first chunk:

func get_avoidance_vector() -> Vector2: var ctr_ray_i : int = int(rays.size() / 2.0) var ctr_ray : RayCast3D = rays[ctr_ray_i] var cluster_colliding : bool = false var bound_low : int = 0 var bound_high : rays.size() - 1 var first_ray : int = clamp(ctr_ray_i - ray_cluster_margin, bound_low, bound_high) var last_ray : int = clamp(ctr_ray_i + ray_cluster_margin, bound_low, bound_high) for i in range(first_ray, last_ray + 1): if rays[i].is_colliding(): cluster_colliding = true break if not cluster_colliding: return Vector2(0,0)In this instance method, which returns a

Vector2, we do the ray scanning. This vector will ultimately have two things, although for this post we really only care about the first: an angle (in radians alongVector3.UP) the NPC should pivot towards to avoid a detected collision. The second part is a speed adjustment, though I’ve removed the code from these examples that calculates that as it’s not germane to the heart of this writeup. In short, if you’re curious: it will cause the NPC to slow down if every option will lead to a collision (in order for the NPC to buy more time for better options to emerge as others move around them), or it will speed them up when the way ahead is clear.It starts out by getting the middle index of the array (the explicit cast doesn’t produce anything different from just doing

rays.size() / 2aside from suppress a debugger warning about the loss of precision from integer division), grabbing a reference to the center ray, and initializing a colliding flag. And it also sets the upper and lower boundaries of the rays array, just so we don’t have to keep repeating the call torays.size()a bunch elsewhere.The method moves on to special-casing the center cluster of rays[7] to see if we even need to worry about avoiding something. Remember earlier that any individual ray in a cluster colliding means the cluster collides, so as soon as we find one that’s hitting another NPC, we set the flag to true and break the loop. There’s no point wasting anymore cycles checking the rest of the rays. One rotten ray spoils the whole bunch.

If there was no collision, the method immediately returns a

0adjustment angle which allows the NPC to continue moving along their originally intended path with no changes. You may note thefirst_rayandlast_rayvariables, which are easy enough to correctly guess that they define the range of rays in the array to consider for this cluster (ctr_ray_iminus and plus the margin). These values must be clamped appropriately to avoid any out-of-bounds errors on the array access, in case the margin exceeds the size of the array. For example, settingnum_rays = 3andray_cluster_margin = 5would lead this method to try to access elements-4 .. 6of a 3 element array. Straight to jail! Clamping these two ray index values to the actual boundaries of the array eliminates this problem. The clamping also plays an important role even when the ray count and margin are set properly. More on that in a second.The next part of the method does something that seems really incredibly dumb at first, just hammering away at batteries levels of stupidity. It takes half the size of the rays array plus the cluster margin (plus one, because

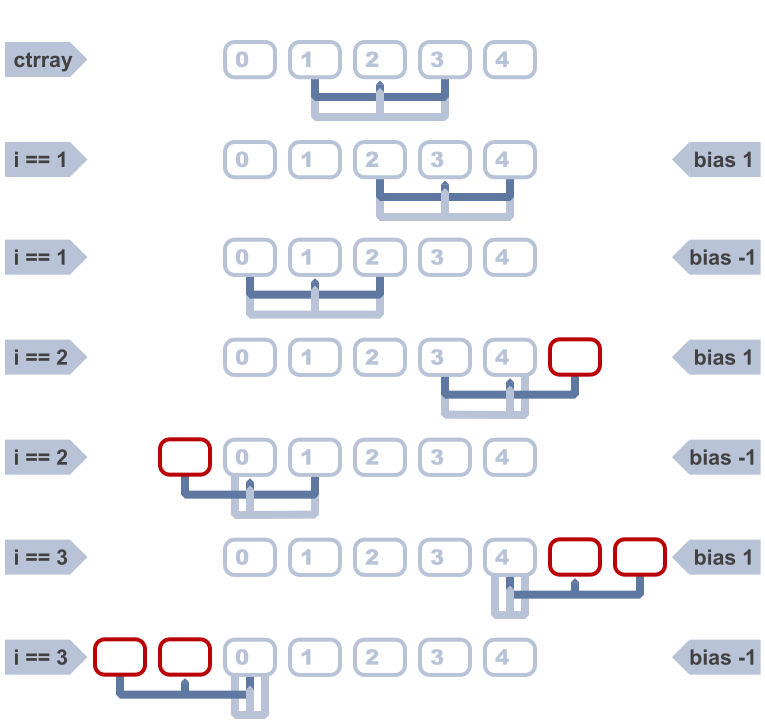

range()loops stop before the final value), makes a range of integers from that, duplicates them, and stores it all in a new array. That seems at best odd, at worst believes in chemtrails scales of idiocy. Except that it’s integral to taking the bias from fifteen chapters ago and using that to dance the salsa, to do a little cha-cha. This can be (and in my full implementation is) done once, whenever the rays array is created or modified, rather than during each avoidance check. But it makes a lot more sense to show it here since the entire reason for it is using it with the bias and the code is the same either way[8].var indices : Array = [] for i : int in range(1, int(rays.size() / 2.0) + ray_cluster_margin + 1): indices.push_back(i) indices.push_back(i)If the NPC has 5 rays and a cluster margin of 1, then the

indicesarray above will end up being[1, 1, 2, 2, 3, 3].0is skipped because we already special-cased the center cluster and it would be a waste to check it again. (Wait, index0is the center ray? you ask. Hold your horses, we’re about to get to that.) Why on earth would we want this? Let’s look at how the non-center ray scanning works now:var bias : int = get_directional_bias() for i : int in indices: var cur_ray_i : int = ctr_ray_i + (i * bias) first_ray = clamp(cur_ray_i - ray_cluster_margin, bound_low, bound_high) last_ray = clamp(cur_ray_i + ray_cluster_margin, bound_low, bound_high) cur_ray_i = clamp(cur_ray_i, bound_low, bound_high) bias *= -1 cluster_colliding = false var cluster_vector : Vector2 = Vector2(rays[cur_ray_i].rotation.y, 1.0) for j : int in range(first_ray, last_ray + 1): var cur_ray : RayCast3D = rays[j] if cur_ray.is_colliding(): cluster_colliding = true break if not cluster_colliding: return cluster_vectorAlmost right away, that funky doubled-up half-the-rays array is what we’re looping over. But that doesn’t mean we only check half the rays, nor are we checking any cluster twice. First we call our buddy from earlier, the

get_directional_bias()method. We call this once before starting our loop across the clusters. Except we’re supposed to be dancing left and right, not just one direction? That’s why we needed the index offsets twice. Offsets being key. Each one of the values inindicesis an offset from the center of the entireraysarray, and with each loop of this check we apply our bias, then we flip that bias for the next loop iteration. So if the NPC’s first inclination is to swerve right to avoid a collision because they’re in North America, but they still collide, then they’re going tobias *= -1and swerve left. Except the second iteration of this loop is still going to have ani == 1like the first one, so the NPC will check the cluster beginning just one index offset from the center ray again only in the opposite direction. It won’t be until the third iteration (anotherbias *= -1to swerve back to the right) thati == 2and the ray scanning will move one more offset outward from the very center.Salsa achieved!

Something you may have noticed is that a 5 element array is going to have an index range of

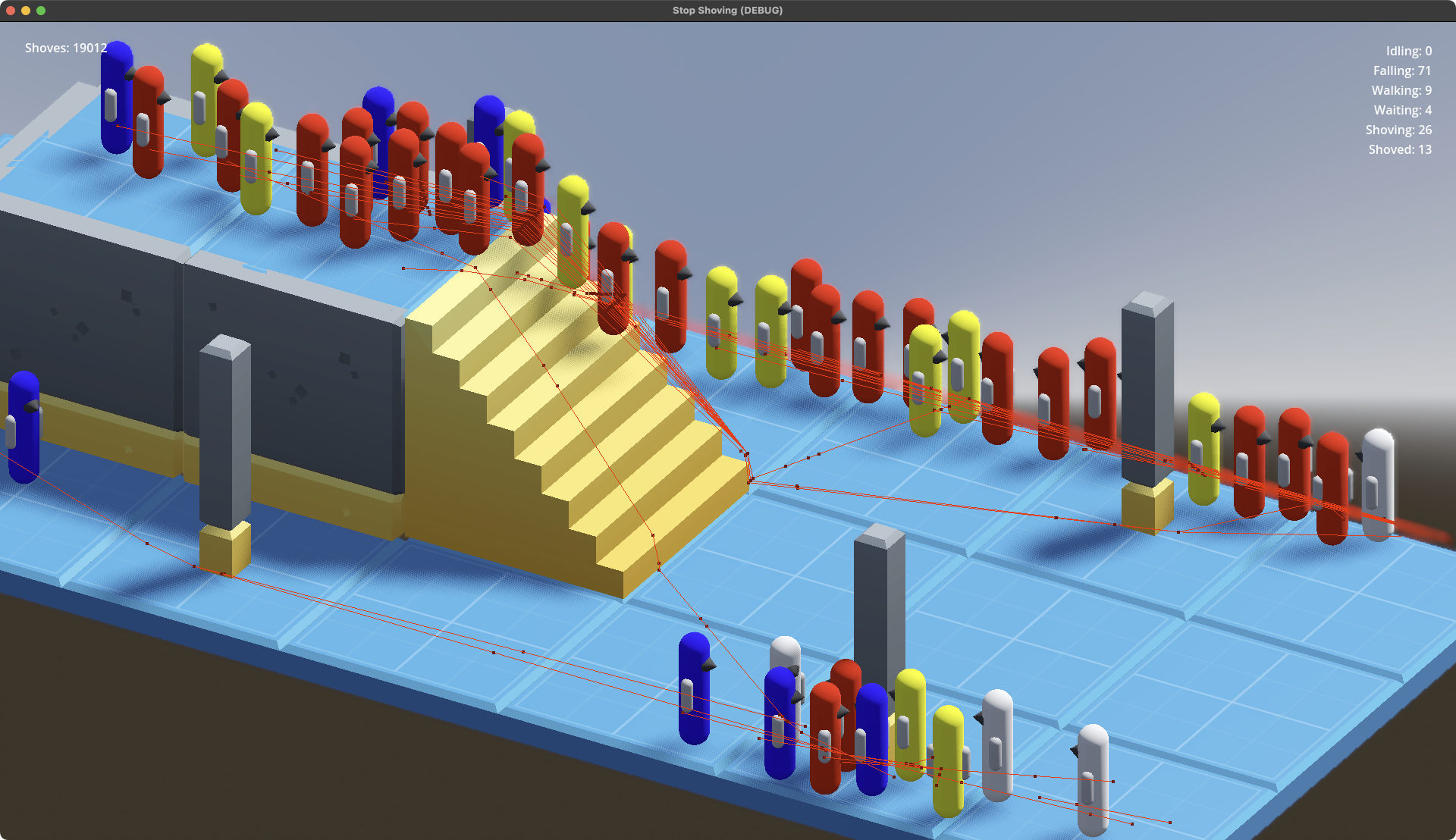

0 .. 4with a center index of2. But our offsets list goes up to3and2 + 3 == 5and even though a certain country abolished its Education Department, the inescapable fact that five is greater than four still applies even to computers there whether the humans believe it or not. Similar to the clamping earlier, thefirst_rayandlast_rayclamps in this loop ensure an out of bounds error doesn’t occur. So why even have the extra numbers (recall that it’s not just one extra offset, it’sray_cluster_marginoffsets)?If you’re a visual learner, the following diagram (click to embiggen) shows the progression of the cluster scans assuming an arc composed of 5 rays with a cluster margin of 1. The darker lines show the pre-clamping index ranges at each cluster, while the lighter lines show the post-clamping range. The arrow-ended line inside the range represents

cur_ray_iin the code snippets above. Red boxes denote the out of bounds indices which clamping prevents. A five ray arc is pretty small, and testing stations yielded pretty poor avoidance results. I’ve generally found 11-13 to be a good compromise so far, depending on the size of the arc, but then this diagram would take up too much space before it got to the good part of showing the narrowing search at the ends of the arc.

At the extremities of the ray arc, if everything has been colliding and the NPC is getting desperate for a way out, smaller clusters that don’t collide are better than nothing. So the offsets go beyond the boundary of the array by the size of the margin, which means we can check successively smaller clusters at the edges of the array all the way down to a single ray.

This is also why we add a clamp on

cur_ray_iitself (but only after calculating and clamping the first and last ray index values), because as the clusters extend off the edge of the array, we have to treat the very first/last ray in the array as the current one.With all these bounds and ranges set up, we can do the same thing we did with the center cluster. Look at the rays and the first one that’s colliding short-circuits the cluster check and breaks the inner loop. The last bit of the current cluster scan is to either return the angle of the center ray if the cluster is unobstructed, or to move on to the next cluster. Then, if all else fails and we’ve exhausted all of the offsets without a non-colliding cluster, there’s a little bit not shown here that returns the

0angle vector with a speed dampener.There’s a few improvements that could still be made. One possible optimization is to memoize or locally cache the

is_colliding()return value so we don’t need to call the method itself multiple times for the same ray when it appears across different clusters. The gains there would be minimal, though, since the collision detection itself was already performed in the physics engine and the method is just returning the result. There’s no extra physics work being performed each time, since we aren’t callingforce_raycast_update()after modifying a raycast inside the same frame.But that hints at another optimization we could investigate: instead of instancing all the separate

RayCast3Dnodes and letting them run continuously, we could instance only the center cluster’s worth of rays (as those get checked every frame currently, regardless, to know whether to engage the actual avoidance procedure). As long as they aren’t colliding, that’s the end of the story for that frame. And when there’s more NPCs in the scene that aren’t on a collision course than are, the savings in nodes could be worth it. However, as soon as that center cluster does collide, the remainder of the method shown above could sweep one ray around to each position, force a raycast update, check and cache the collision value, and do so until a non-colliding set of angles that make up one of the clusters is found. Reset the ray to its original position (for the next frame) and send the avoidance angle back.Assuming the overhead of raycast update forcing is minimal, that could be a performance win by limiting the number of raycast collision detections per frame to the actual minimum necessary to keep NPCs moving freely. Something for the backlog, since the current method has been plenty performant in testing so far. I’ve got much bigger fish to fry from the flame graph than that right now.

Another optimization that I haven’t implemented yet, but plan on adding, is skipping avoidance checks on various frame intervals. I have a similar optimization on other sometimes-expensive systems in the simulator already and done with the right finesse in choosing intervals, the performance benefits are pretty noticeable. The idea is simple: count down every frame from a desired interval value and once you hit zero, do the thing, reset the counter and repeat. You only do the expensive calculation every N frames, and because NPCs aren’t spawning on a global interval boundary (i.e. they spawn whenever they spawn, not strictly at

ticks_msec % 1000 == 0or some nonsense like that) their counters will tend toward a natural jitter, thus evening out the load on the engine without any additional trickery.The catch is figuring out what you can safely do on intervals like that, and how large those intervals can be before the system breaks down. Having NPCs only perform their avoidance checks every 5 seconds would vastly reduce the computational cost of the system, but it would also render it useless. Having them check every other frame might sound like it makes it half as costly, but then you have the slight overhead and the added indirection of the counters. But NPCs could probably get away with only checking for avoidance adjustments once every 5-10 frames until they start detecting collisions, and then ramp it up to recheck more frequently until the coast is clear again. Is the savings from doing one fifth to tenth the calls to

get_avoidance_vector()(but still having the arc of rays persistent) enough? Seems reasonable to assume it will be, but only some profiling will tell.So, that’s the basic Sidewalk Salsa avoidance system between NPCs in about five hundred nutshells. As always, if you read through my entire incoherent rambling, I’m both impressed and a little bit terrified! If you’d like to see more, if these table-breaking treatises are interesting or provide any value to you, I’d love to hear about it. Contact info is on the About page. And if you somehow find enough value in these screeds to unlock a bit of generosity, I’ll never turn away a little support.

Don’t come at me for possibly choosing the least apt position for this example. I know next to nothing about the game beyond it involving Very Big Guys running into each other so they can get the Most Brain Injuries trophy. ↩︎

Segue schmegway. ↩︎

Being developed in Godot, the examples here will use nodes and language features of the same, but almost everything here has a direct or very similar counterpart in other engines. ↩︎

But make sure you choose a default that is odd, as the custom setter won’t intercept and fix that; only subsequent assignments. ↩︎

Mostly. As always, rude or misbehaving NPCs can flout the defaults by inverting their behavior under the right conditions. ↩︎

Where that limit is higher than what a bunch of persistent

Area3Ds can handle but low enough that shapecasting remains performant. Perhaps we’re building something that just needs modest numbers of NPCs at a time navigating hallways, where we also want to make sure we only detect things on the same side of the walls as the NPC. This still wouldn’t work for hundreds or more in an expansive transit concourse. ↩︎Sidebar: At least half the bugs I end up catching in my code are me forgetting that

range()produces a list that includes the start but excludes the end. I should submit a PR to Godot that adds arange_that_does_what_you_thought()method. Case in point, theforloop in that snippet left out the required+ 1until I was editing this post. ↩︎Just make sure

indicesis accessible by both methods by making it an instance property instead of a method local variable. ↩︎

4888 words posted - Permalink

-

One Does Not Simply Walk Into a Subway Station

I started greyboxing out some basic station shapes, because at some point I’m going to need to wrangle those Blender shortcuts and what time is better than now to start practicing? As part of moving from the quick and dirty GridMap setup (that was enough to get the first pass on mechanics working) I decided it was also time to tackle the full station routing system (and not just the two-floor-one-staircase placeholder I had slapped together previously).

NPCs don’t spawn at an entrance, or eventually within arriving trains, and just plot a direct course to their final target. A naive system, that might work well in a shooter where you just want enemies to chase down a player, could leverage the

NavigationAgent3Dsystem with aNavigationRegion3Dcovering the entire station. Just keep telling it theVector3you want the NPC to reach and let the nav agent blackbox do pretty much everything for you. Set up the mesh and agents well and it’ll work. With one catch: it’ll work every time. The NPCs will get a navigation path that takes them on a reasonably close to optimal walk through the level, and every NPC one after another will follow those same worn paths. Give them the same train to catch and they’ll just be a giant line of ants marching in single file through the station.The next step up from that is to paint paths through a level, and that’s an incredibly common approach in open world games. NPCs get a bunch of invisible corridors overlaying a map within which they have some room for deviation, but still effectively put those NPCs on rails between various sets of points. The paths can be laid out to look natural if all you do is watch a single NPC follow them. But in the end they’re still tying NPC movement to predetermined routines, and after you see the fifth NPC take the same steps it becomes apparent there’s no actual variation or chaos behind it.

Just as in the real world, the NPCs in Stop Shoving! aren’t going to, nor should they, take the optimal paths. And it’s more than just trying to avoid all the other NPCs moving around. The first time you’ve visited a new city and you’re trying to get from the hotel to a museum, did you enter the subway and know right where to go? Coming home late because you grabbed some drinks with friends, and then realized halfway up the stairs to the street that it was your anniversary and you better have some of the most beautiful flowers in hand or else, and wasn’t there a florist at the other end of the concourse? Or your train’s severely delayed and there’s a restroom one floor up and you may as well since you have plenty of time and a weak bladder. Maybe you just spaced out and walked to the south platform instead of the north.

So NPCs need to be able to move around dynamically, navigate a fluctuating set of Player-induced obstacles, change their minds, and most importantly: get things wrong sometimes. And all in ways that are more realistic than just picking random points in the station and then finding the straightest, shortest line between them. But how can you design a system to get something wrong unless you know what’s right?

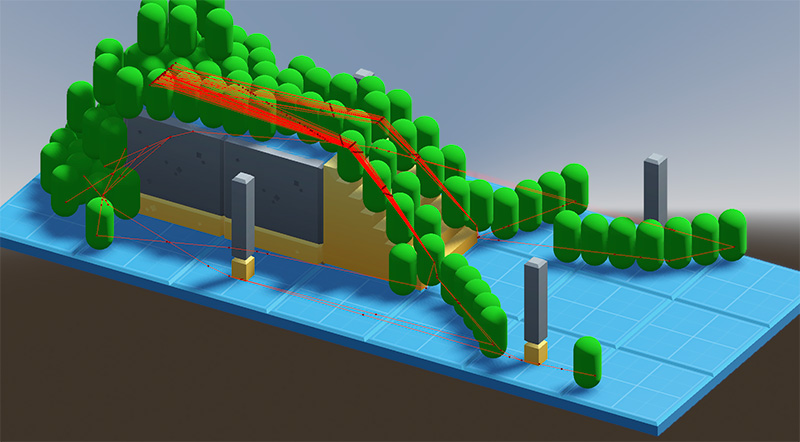

The first step is to have a reasonably chunked map of the station that can form discrete areas in which decisions about behavioral changes can be made that are at least somewhat contextualized. NPCs shouldn’t get bored waiting for their train when they haven’t even made it past the turnstiles yet. They probably shouldn’t run back up to the concourse after reaching their target train’s platform just so they can go on a pastry shopping spree (wouldn’t blame them, though). Given that, stations need to be sectioned off into platforms and floors, and floors need various types of conveyances to connect them - stairs, elevators, and so on - and all of it together ends up forming a strongly-connected, directed cyclic graph. The floors are nodes, the connectors (stairs, etc.) are the edges, and in real-world stations there is always at least one path from each node to any other, even if it would require the NPC to retrace their steps back to a starting position out on the sidewalk.[1]

I’m fortunate there’s already deeply researched ways to figure out what paths exist in all sorts of graphs. Most commonly they’re used to find shortest or optimal paths, and in fact the built-in navigation support in Godot (and most game engines) relies on modified Dijkstra’s and/or A* algorithms. Almost all of them are focused on shortest paths or just sheer computational efficiency, but we can start with a recursive DFS algorithm, toss in cycle checks, calculate weights as we go, and get something that serves this game’s “give me as many paths as possible and make some of them slow and inefficient!” needs. It’s a variation of Tarjan’s strongly-connected components algorithm, but rather than detecting all strongly-connected subcomponent graphs its aim is to discover all non-cycling components between two arbitrary nodes. This algorithm, in a way, is returning a collection of halves of what Tarjan’s does, because we don’t need to get back to our starting point each time, we just need to make it to any arbitrary mid-point.

The approach now is pretty straightforward, and it’s completely automated as long as I put the

Area3Ds in the correct spots to register floor/stair/elevator/track connections[2]. Upon level loading, the station collects all these area designators based on their collisions, and can build a dictionary of adjacencies such that every single floor and conveyance has an entry in the dict, and their corresponding values are an array of every outbound connection. Outbound only as this is a directed graph, since things like escalators (an edge between two floor nodes) only move in a single direction. Because it’s based on automatically scanning for overlapping areas, there’s no special configuration for any level and the routes generator doesn’t care if the station has one floor or a hundred[3]. It just gets a bunch of adjacencies in a data structure that looks like this if created directly instead of constructed dynamically from colliders and areas (full object references trimmed down/out for readability):var adjacencies : Dictionary[Node3D,Array] = { "floor1:<SSG_Floor@23...>": ["southstairs1","southstairs2","northstairs1","northstairs2"], "floor2": ["southstairs1","southstairs2"], "floor3": ["northstairs1","northstairs2"], "southstairs1": ["floor1","floor2"], "southstairs2": ["floor1","floor2"], "northstairs1": ["floor1","floor3"], "northstairs2": ["floor1","floor3"] }

Or if you’re a visual learner, that adjacency mapping is what this test station looks like as a cyclic graph. It’s directed, too, but since I’ve only implemented stairs, which are two-way, you can’t really tell in that data structure. Once I have working escalators, you would be able to infer the directed nature of the graph by non-paired edges. That first entry in the dict indicates that the

floor1object (anSSG_Floor, but the dictionary keys are typed toNode3Dbecause they can be either anSSG_Flooror anSSG_FloorConnector(or rather, one of the conveyance-specific subclasses of it) and those classes only share a common root at Node3D) has four outbound edges:southstairs1,southstairs2,northstairs1, andnorthstairs2. It says nothing about where those edges lead. That’s where the graph traversal comes in. The recursive, depth-first traversal function can descend into each of those edges, and repeat that process until it finds its destination at which point it has a fully constructed path that can be added to the cache.But how does it know its destination (or its origin for that matter)? A separate data structure was built just outside the route generator:

var routes : Dictionary[SSG_Floor,Dictionary] = {} for from_floor : SSG_Floor in station.floors(): routes[from_floor] = {} for to_floor : SSG_Floor in station.floors(): if to_floor != from_floor: routes[from_floor][to_floor] = SSG_RouteSearch.get_routes(from_floor, to_floor)You might cringe at first at the nested loop building a dictionary of dictionaries that is the square of the floors present in the station. But two things should quell that misplaced revulsion:

-

How many subway stations can you count that have more than a couple dozen floors, or even half a dozen?[4]

-

This is a one-time generation and memory cost for the sake of super fast simultaneous lookups by an arbitrary number of NPCs, when those lookups need to happen during the time-sensitive physics process of the simulation.

This will spend, at worst case, maybe a few hundred milliseconds at level load and a megabyte or so of memory to give single digit microsecond route lookups even in a station with dozens of floors and more elevators than you can shake a counterweight at.[5]

So now that we have our station represented as a directed cyclic graph encoded into an adjacencies map (which, remember, required no special setup other than the meshes for floors and stairs having the appropriate Class assigned to them - easy-peasy!) and we have the list of every pair of floors that exists, we can start to call that route generator (which is actually done in the very last line of the code above at the innermost part of the nested loop). That recursive DFS is as simple as this:

static func get_routes(from_floor : SSG_Floor, to_floor : SSG_Floor) -> Array: if from_floor == to_floor: return [] if not (Adjacencies.has(from_floor) and Adjacencies.has(to_floor)): return [] var routes : Array = [] for adjacency in Adjacencies[from_floor]: get_next_step(routes, [from_floor], adjacency, to_floor) return weighted_routes(routes) static func get_next_step(routes : Array, traversed : Array, next : Node3D, dest : Node3D) -> void: if next == dest: traversed.push_back(next) routes.push_back(traversed) elif Adjacencies.has(next) and not traversed.has(next): traversed.push_back(next) for adjacency in Adjacencies[next]: get_next_step(routes, traversed.duplicate(), adjacency, dest)There isn’t really anything impressive happening in there. But there are a couple important things to note. The first is the cycle checking, which is handled in the

traversedarray that gets passed into each recursive call. It also functions as our constructed path, a copy of which gets pushed onto the end of all the discovered routes every time the destination floor is reached. If things got really bad, we could even use it as a way to limit recursion depth with a quick short-circuit whentraversed.size() > MAX_RECURSION.Any adjacency which is not the destination floor gets a quick check that we know about it (just a little extra paranoia that really only covers the case of a broken station layout) and that we haven’t seen it before. That’s the actual cycle check. If it passes those tests, then hooray, we’ve stumbled upon an undiscovered path! It’s added to the traversed array, and now all we have to do is get all the adjacencies of that entity in the graph and repeat the entire process over. Note that every single call into the recursive

get_next_step(...)function receives a copy of thetraversedarray, not the original. This is critical for the back-tracking piece of the DFS algorithm, otherwise we’d have this one endlessly-growing (and very much invalid) path at the end of all this. Each level down in the recursion starts off with the last graph component before the recursion before it.In the end, every non-cycling path between every single floor pair in the station will have been discovered and cached for lookups later. All an NPC needs to know is what floor they’re on and what floor they want (or think they want) to be on, and one nested dictionary lookup later they have an Array containing every way to get there, which looks like this:

{ "floor2": { "floor3": [ { "route": [ "southstairs1", "floor1", "northstairs1", "floor3" ], "cost": 48.6 }, { "route": [ "southstairs1", "floor1", "northstairs2", "floor3" ], "cost": 28.0 }, { "route": [ "southstairs1", "floor1", "northstairs2", "floor3" ], "cost": 28.0 }, { "route": [ "southstairs2", "floor1", "northstairs2", "floor3" ], "cost": 48.6 } ] } }That snippet shows just the portion for paths originating from floor2 and ending at floor3, but the fully constructed routes cache includes similar entries for all floor pairs. Once the NPC decides which of the routes to use, they’ve got a handy-dandy pop()-able array of navigation targets. My next target is a floor connector so query it for an ingress point that’s located on my current floor.[6] And now the NPC knows where to walk in the sub-region of the station in which they’re currently located.

Final note, since I’ve definitely rambled on too long already: what’s that

costentry? That’s how NPCs can rank the paths. It’s a sum of all the weights for every edge and node in the route. In a shortest-path graph traversal algorithm like Dijkstra’s you’d get a single path back that would have been one of those with the cost of 28.0. But a thousand years ago near the beginning of this post, I laid out a requirement for this route generator: the NPC navigation system needs to know about multiple paths, including the bad ones.The weights that go into that final cost include things like the distance an NPC would need to walk (in the example route data above) along

floor1to get from thesouthstairs1to thenorthstairs2as well as the relative movement cost of using whatever conveyance connects different floors. Stairs are more cumbersome to use, so the same distance in meters on stairs costs more than walking along a flat floor. Riding an escalator costs less than walking. Elevators have costs based on not just the distanced traveled, but how many floors they might need to stop at along the way (or stop at before they can even pick up the waiting NPC).Thus, an NPC with high perception or one which finds itself surrounded by navigation hints in the station will have a much higher chance of selecting a route that is cheaper. NPCs suffering from confusion have an increased risk of selecting a more costly route. I’ve left the actual calculation of those costs out of the code above because it’s highly specific to this game’s simulation, and would be a distraction to the route generation rambling here. It’s also still undergoing tuning.

There’s one more thing with the routes generator[7] I haven’t implemented yet, and will probably wait until I build more conveyance types, which is accessibility flags. An NPC in a wheelchair or dragging a 40kg suitcase is going to want a way to filter out routes that use stairs and strongly favor ones that only have elevators, ramps, and maybe escalators. That will probably take the shape of a bitmask that sits within the route dict, alongside the

routeandcostentries, but for now that feature is just a backlog item in Jira.[8]Anyway, I hope that all was interesting. It probably wasn’t. You have my deepest concerns and sympathies if you made it all the way through. This has served its only real purpose, though, which is that I think better when I try to write it all down.[9] I fixed a couple minor bugs and made one performance improvement just in the course of these more than 3,000 words.

I suppose a station could physically have a floor only reachable by a one-way escalator with no egress conveyance, but no public mass transit system is going to be able to violate their locality’s fire and safety codes like that. ↩︎

I think I’m going to make that a whole separate blog post later, because this one is running way too long already. ↩︎

Eventually it will care, but this setup is done once per level and then cached for speed during gameplay. On my main development machine (a 2013 M2 Max Macbook Pro that has Godot, Blender, VSCode, Photoshop, Bridge, and a thousand Firefox tabs all running simultaneously) it runs in milliseconds even in larger station structure tests. ↩︎

I have a little note tucked in the back of my game design doc that the two Final Boss stations will probably be Seoul Station from Seoul, South Korea and Shinjuku Station in Tokyo, Japan. I did get pretty good navigating around a solid chunk of the nearly 800 stations within the Seoul Metro over the course of the nearly six months I stayed there in 2024 and early 2025. Shinjuku Station, however, defeated me every time. I’m going to chalk up my countless humiliations there over the past couple years to the ridiculous amount of construction they have going on. ↩︎

In this sample station, which is admittedly very small, the entire route generation process takes under 100μs. But yes, the math nerds reading this will scream, “Recursive DFS doesn’t run in constant time!” and that is absolutely true, but I’ve mocked some dummy stations with plenty more floors and connectors and for real-world station layouts we’re still talking sub-millisecond to double-digit milliseconds in extremis. And the nested dictionary lookups take under 2μs each time an NPC needs to pick a route from the cache. ↩︎

Or for rude NPCs, they can query for an egress point that also allows ingress - in other words, walking down the culturally-inappropriate side of the staircase and thus getting in the way of NPCs with higher social cohesion. I’ll probably go more into that in a later blog post about how floors and conveyances are constructed inside levels. ↩︎

Final-final8_Done_blogpost-lastrevision-1(Ready_to_publish)-Reviewed.md ↩︎

Gods save me, but yes, I’m using Jira on a solo dev project. Don’t ever let anyone accuse me of practicing self-care. ↩︎

Not that anyone would ever be able to tell from the poor quality of the writing. ↩︎

3056 words posted - Permalink

-

-

Midnight Train to Georgia

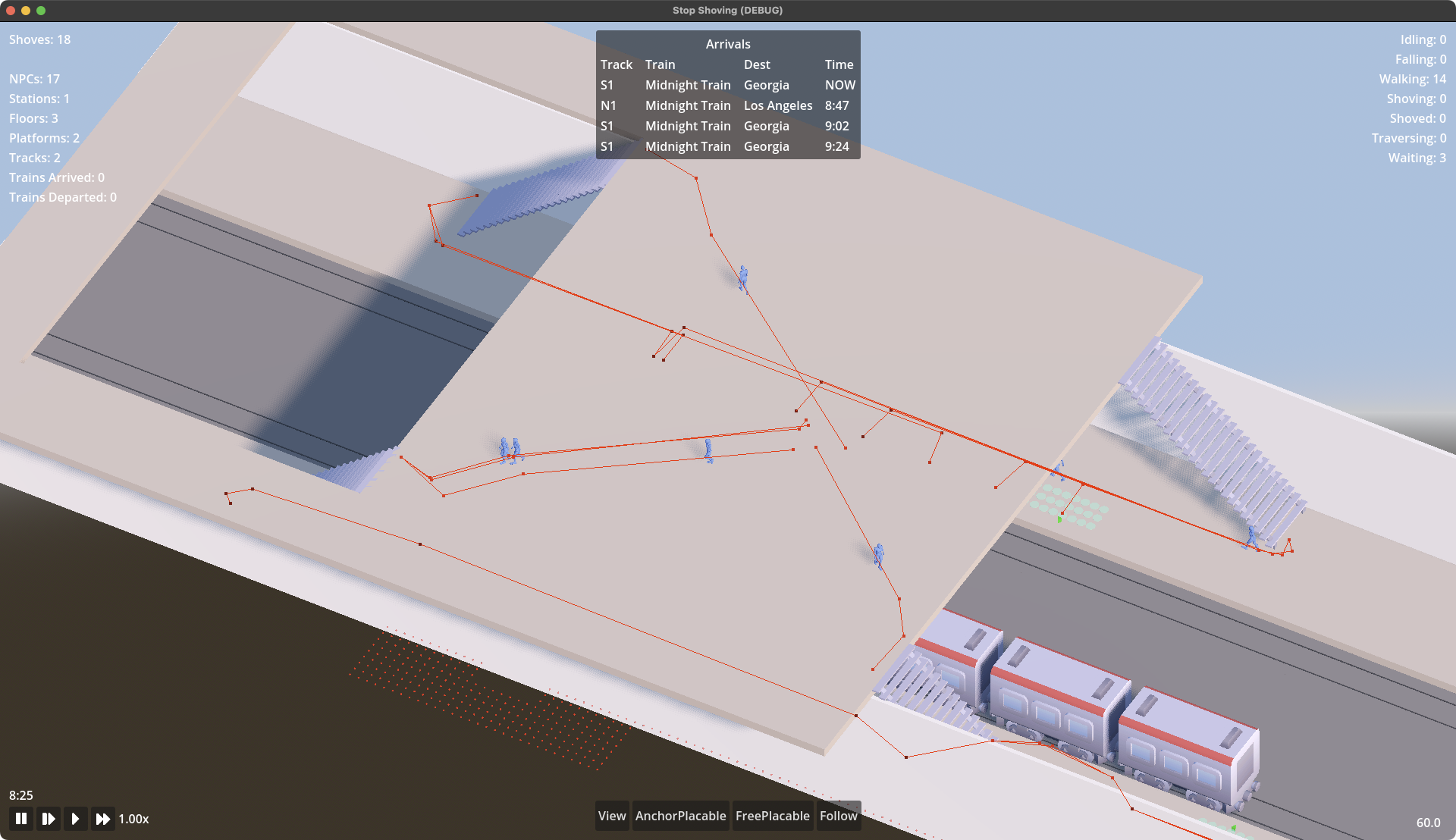

Finally took some time away from tinkering with NPC navigation and editable objects in Stop Shoving! and decided to work on a really minor, nearly inconsequential feature of the simulated world of subway stations: the coming and going of trains.

NPCs can’t board them yet, but they can be hit by them and that’s a start!

Part of the eventual scoring mechanic involves NPCs reaching their intended train in a timely manner (and the gameplay loop for the player involving managing the obstacles and available interactions along the way) and successfully boarding it. This means trains in the station aren’t just random actors showing up at whatever platform(s) exist and letting whatever NPCs that happen to be nearby board and be ferried out of the subterranean gameworld.

The trains belong to specific lines, traveling to specific places, and each and every NPC that inhabits the station cares about those details. How they get there will be the topic of another post as I fill out the station navigation (right now it’s stubbed out to allowing traversal across up to two floors via up to one conveyance (stairs, escalator, etc.)). How and where and when the trains move is the point of this one.

A few requirements:

- A track can host more than one train.

- A track can belong to one[1] or two platforms[2].

- Only one train can be present in the station on a track at any given time.

- If a train is scheduled for arrival and the platform is occupied, the arriving train must be delayed until the platform clears and then it should arrive promptly.

- If multiple trains are delayed, they should arrive in the order they were delayed as each prior one clears the track.

- Upcoming arrival times for at least the next N trains should be known so it can be broadcast through arrival boards.

- Every train should have its own schedule, and that schedule should vary throughout the day (rush hours, etc.).

- Trains within the station should also broadcast more granular statuses about the stages of their arrival, boarding, and departure so that all concerned NPCs can react appropriately.

Luckily, part of the infrastructure for this I had already built as part of managing the simulation speed controls: the internal game clock. Godot has a built-in

Engine.time_scaleproperty which is ideal for adjusting the overall speed (or paused status, by setting to0.0) of the simulation, but layering anSSG_GameClockclass atop it allows for useful things like making in-game days consume a fraction of a real-world day even attime_scale = 1.0. Even more helpfully, it allows all manner of entities to connect to signals from the game clock for time-based triggers.SSG_GameClockemits signals on every in-game second, minute, hour, and day change that is wholly apart from the need to instance and manage a bunch ofTimers[3].Trains now get to subscribe to a per-minute signal from the game clock, and maintain a simple

Arraybased queue with a configurable size. As long as the array is that minimum length, all is good, and if not then the difference determines how many upcoming train arrivals need to be scheduled. The last-scheduled time is passed along to the Train-specific scheduler which can examine time of day (to adjust arrival rates based on things like increased rush hour service levels or overnight suspensions of service) and pick an increment from the last arrival to use for the next.In this same trigger, the Train can check whether it should have an arrival in progress. If so, it can make a call to its parent

SSG_Trackwhich does the checking of whether a train is already in the station to decide whether to initiate the new train’s arrival immediately, or place it in another queue for delayed trains, which ensures that all the trains which tried to arrive while the platform was still occupied can be dispatched in the correct order as it clears.And all of this can get hooked into by an arrivals board singleton that can package it up into what a human racing through a busy subway station would have access to should they have a moment to check a display: a fixed-length list of current and upcoming trains and their platforms that lets one know whether you can saunter lazily along the hall and down the stairs for your ride to work, or whether you need to make a mad dash for it to avoid getting yelled at by your arsehole boss Gary for not making it to your shift at the misery factory on time.

Lastly, if there’s a game clock, seems simple enough to hook that up to a world environment to get the sun in the right place and the sky the right colors. I don’t anticipate putting a whole fancy volumetric cloud system into the game, given that almost all of it will take place not only indoors, but underground, but having that little touch of ambient golden hour sunlight coming into the station as the crowds from the rush hour madness filter their way out seems like it would be a nice way to fill out the atmosphere of the game.

I should probably start putting some lights inside the testing station before I put a roof over it, though.

Imagine two platforms, say a South and a North, with two tracks in between them. Each platform serves one of those two tracks, and from a train on either of them a passenger could only alight from or depart to one of the platforms. ↩︎

Imagine a split platform that has only one track running through the middle. A passenger on the arriving train could disembark to either side, and passengers from either platform could board the train in the middle. ↩︎

There are still many things in the simulation’s codebase that are Timer-based, of course. ↩︎

1071 words posted - Permalink

-

You Keep Me Anchored

Stop Shoving! isn’t going to just be a rail station simulator that passively allows the user to watch a bunch of NPCs push each other around. While I won’t give away the entire gameplay loop this early, a core mechanic will center on the player’s modifications to the platforms and surrounding areas which will impact NPC behaviors in various ways.

To support that, I have to build all the in-game functionality to modify the level on the fly. Being one person, I don’t have the time (let alone attention span) to embed the equivalent of a full featured 3D world level editor that gives players unfettered access to the level meshes, physics bodies, and event processing code to remake each level. It also would make for a tremendous and off-putting learning curve. So I’ll do what a thousand games before have done, which is let the player drop predefined objects onto the level in predictable and simple ways.

Countless games give players a way to place blocks on a grid whether that grid is squares or hexagons[1] and those blocks are city zoning districts or dirt and wood voxels. Why fix what isn’t broken?

The wrinkle is the blocks are going to be a variety of irregular shapes and they’ll be actively interfering with the physics processes of an arbitrary number of NPCs in different ways during different phases of the player’s use of them to modify the level. Plenty will have simple square footprints, or at least rectangular. But they won’t all be the same dimensions along a side. And there are some, maybe many, that will be more complex polygons. Some may have insets or outsets at various heights, others with passages through them that may or may not allow blocks to be placed within. Some will immediately instantiate and trigger NPCs to adjust behaviors right away, others will require a delayed phase-in that impacts NPC actions differently as the phases progress.

How to go about something like this in Godot? Let’s start with just the placement part of it and leave the impacts to NPC behavior for later.

The

GridMapnode and associated functionality hint at a promising starting point. And the approach I’m taking does lean on them a little bit. For now, the station structures (the platform, entry points, track beds, walls, and so on) are assembled using a grid map. It makes painting a library of meshes into a 3D space and generating collision objects quick and easy (compared to instancing and transforming a ton of individualStaticBody3Dnodes, at least). The grid map level design approach also makes it much easier to modify and maintain the station structures as I slowly fill out the protoyping mesh library during development.But there’s a lot of gotchas in then using that GridMap as the editable base for the player in-game. Each cell in a

GridMapcan contain only a singleMeshInstance3Dand those cells, without writing a new class that extendsGridMapand implements this, don’t have the ability to track metadata on what a user is allowed to do inside that cell. I don’t want the player to add a bench that floats in the air. Or a vending machine that juts out in front of where a train needs to pass.[2] I also don’t want the player to just be running about replacing platform floor meshes with empty voids.So, do I write a

PartiallyPlayerEditableGridMapWithCellMetadataclass that extendsGridMapwith all these constraints? Or do I do what I’m doing, which is build the static elements with aGridMapand then layer a bunch of anchor points through the areas that players can modify, and provide a library ofStaticBody3Dobjects which can be attached to sets of these nodes? It’s the latter, as the screenshot above probably gave away. This is working well during the early stages of development. One grid map contains the static elements of the level, and a second grid map is used to paint anchors everywhere necessary (and removing ones that should no longer exist because I’ve decided to add a staircase or a pillar or something else where previously there was space for the player to add their own objects).

It does add a bit of work in the scene instantiation, where the level’s

_ready()method needs to scan the second grid for non-empty cells and instantiate anSSG_AnchorPointnode for each. I have an optimization todo for down the road to bake all this into a much more efficient data structure at build time and that during runtime doesn’t useArea3Dmethods likehas_overlapping_bodies()to figure out whether anchors are aligned with available anchor points. But it’s a one-pass operation at level instantiation and during testing has been performant enough even when I’ve littered a station with a couple thousand anchor points.It’s Good Enough to unblock me to move on to the more interesting parts of the simulator, which includes working on the NPC behavior strategies to navigate around obstacles and each other (or in the case of aggressive NPCs with low social cohesion, navigating into each other), and probably as the next big step after that working on NPC-interactable player objects (beyond collisions).

Indisputably superior to squares in every conceivable way. Give me a monochrome hextile srpg with no storyline and an all-vuvuzela soundtrack and I’ll play the hell out of it. That’s how horny for hexagons I am. ↩︎

Well, okay, maybe there are some exciting opportunities in a creative gameplay mode. ↩︎

1015 words posted - Permalink

-

Shoves Per Second

The shoving simulator is coming along, and in the process I learned an important lesson about physics body name collisions that made me think I was completely failing to grasp how colliders worked. After a couple pulled hairs, it turns out the all-too-simple solution was to use groups for limiting collider effects rather than keying on object names.

Multiple layers and masks might seem even easier at first, but the engine’s collision detection needs to handle a lot of things that can’t be shoved (walls and pillars, for example). The masking approach breaks down unless every NPC gets two collision objects; one for basic game world physics and another for interactions with other NPCs. Which is doable, placing each in different layers, but is more unnecessary work than just taking advantage of groups.

For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction.

Just as importantly as shoving starting to work, so is the recoil and recovering. Bringing a little bit of added chaos to crowded situations, one NPC shoving another doesn’t just push the latter out of the former’s way. The shover and shoved both gain some distance from each other out of the initial interaction, and have the chance of colliding into others around them. This can (and does in debugging runs) lead to chain reactions of a room full of ping-ponging NPCs. Because I’m not yet placing any limits on new NPC spawning, letting it run for a couple minutes nearly guarantees a scene full of physics bodies bouncing off each other hundreds of times per second, only slowing down when a bunch of unlucky ones get knocked off the limited floorspace into the empty void below.

With this basic mechanic functioning, the next steps (I think) will be more robust destination selection for NPCs. Right now the prototyping scene just has a handful of targets and each NPC is randomly selecting one of them to walk toward and stand on. I may also consider starting to work on a way for NPCs to exit the scene that doesn’t involve them falling to their deaths. At least not all the time.

395 words posted - Permalink

-

Hat in Hand

I finally got around to setting up a small Ko-fi account a little while ago, but waited a bit before linking it and waited a little bit longer than that to actively say anything about it. Partially because I wanted to pre-load it with at least a couple things (and test that I had it set up at least somewhat properly) first.

But mostly because I’ve been waffling on whether to do anything with it at all given our rapid descent into economic nightmares, more forever wars, and that paying for groceries and healthcare and a million other things is more urgent than indulging in tokens of support for one random person’s creative pursuits.

Some inspiration came from Posting from Taiwan at the End of the World a few months ago by Faine Greenwood which I’ve had in the back of my mind since. Contacting local, state, and national officials, voting, showing up for group and mass actions, and trying to help within the community where I have some usefulness are all sort of baseline activities. But I, like many others, will go insane (or fall into an inescapable pit of despair) if I don’t have personal outlets as well.

Where I’ve settled is that even though some people claim to place little to no value on art, and specifically photography, I do place a value on my work. Not just the actual and rapidly increasing cost of lenses, memory cards, editing software, and so on but the tremendous time and energy to find somewhere interesting and sit with it long enough to capture something that feels worth sharing.

The value I place on it isn’t some immutable, incontrovertible, objective truth, a measure by which anyone who disagrees or values differently is summarily judged wrong. But it carries at least a little bit of weight. While my primary motivation to capture photos is to be able to leave some record of the world as I’ve been fortunate enough to experience it, not to become another like-and-subscribe prattler[1], if someone else out there shares in notion that it’s worth a little bit, well who am I to get in the way of making this a sustainable pursuit?

As for what exactly could be put on offer to make tossing a few bucks or kroner or yen into the hat, I’ll admit I’m not feeling exceptionally inventive right now. High/full resolution copies is an obvious (to me, at least) option and I’m setting aside selections from the trove of images in my archive to do just that. Maybe discounts on prints when I get that set up at some point? Raffles for puppy playdates? That last one seems legally questionable, and I don’t want to add “find a lawyer specializing in international sweepstakes” to my todo list. Maybe that can be a freebie for anyone who happens to be local-ish and able to figure out what dog parks the twins frequent[2].

I’ll try to think of a few things that would be maintainable and not devaluing. If you somehow exist, and even more wildly unimaginable are reading this, and have an idea or three please don’t hesitate to reach out.

648 words posted - Permalink

-

The Paths More Traveled

In working on Stop Shoving!, one of the earliest problems to solve (or at least one of the earliest ones I’ve decided to try solving) is pathing and collision behavior. The title alone should hint that simulating this will be a central mechanic of the game.

In Godot, the engine I’m currently using to develop the game, basic agent paths and collision detection are generally straightforward for

RigidBody3DandCharacterBody3Dnodes. A lot of the math that developers of yore had to wade through directly is almost completely hidden from a modern gamedev. But they’re designed for things like a weapon or projectile hitting a target, a mob touching the player, walls and other scene objects not letting the player simply pass through them, and so on.

They aren’t designed to fully and transparently automate what I have in mind. Randomly spawned NPCs selecting from a variety of locations they want to navigate to, some of which may be occupied presently or by the time they arrive, as well as steering clear of all the other NPCs around them doing the same thing (sometimes to the same sometimes to other locations they’ve chosen). All in a terrain that may be changing around them. Bridging that gap isn’t too much of a burden and isn’t going to require too much more than checking bounding areas around destination positions for existing occupancy and casting rays about to detect and avoid impending collisions.

But what they definitely aren’t designed for is to have some of those NPCs angrily shoving others, some of them pushing back to avoid being thrown into undesirable spots, pairs of them doing that awkward sideways dance[1] we’ve all done on the sidewalk when neither party can figure out which direction to shift to get out of the way, and so on. There’s also no confusion or indecisiveness properties I can just slide values around on, but people navigating public spaces frequently exhibit varying degrees of both those things, and the envisioned gameplay loop most certainly has those playing important roles in NPC behavior.

Who hasn’t stopped dead in their tracks in the middle of the sidewalk, thrown into a deepening spiral of ennui and wondered, “Do I really want to go to work today?” Or turned themselves around half a dozen times looking for a departures board in the main hall while half the city runs and shoves their way past. Maybe stood on the wrong side of the platform only to realize the mistake two seconds before the doors to the train we intended to board close 5 meters away.

The engine will of course support all of these things, but it’s going to take a lot of custom work with the colliders and physics engine. And so much vector manipulation. Speaking of which, enough rambling, I need to go figure out how to apply a Rudeness Coefficient to a

Vector3.

I believe it’s formally called the Sidewalk Salsa. At least by a few of the research papers I’ve been studying. ↩︎

555 words posted - Permalink

-

The Curious Case of the Missing Comments

Everything everywhere supports comments, reviews, likes, upvotes, downvotes, and quote-replies. They’re the building blocks of engagement, and isn’t engagement all that matters? Who knows what the future ever holds, but I do know in the present at least I have little interest in public commenting or feedback functionality as I build this little thing out.

The simplest reason why is technical. To add any sort of feedback functionality, whether it’s full blown commenting or a humble like counter, to a statically generated site would require adding external calls to the relevant pages. I could pretty quickly toss together a counters API with a comically small Cloudflare Worker (the wrangler config would probably dwarf the counter logic), but I’d rather eat glass than build something that mimics the TikTok clone that used to be for sharing selfies with friends. And unless I want to also build and host my own commenting service (at which point, why run this as a static site at all rather than just use WP), that means a third-party service. Someone else collecting visitor data, executing client-side javascript, and scattering adtech tracking all over the place.

The less technical reason is the time and energy it takes to be a moderator, even when done at a teeny, tiny scale of a site like this. Third party moderation cannot reliably replicate my personal values or judgments on what should stay or go in a commenting section, no matter how many dials their system might offer or how many gigawatts their models consume. Captchas, requiring account signups, keyword filters, and other one-time costs to manage a commenting feature are ineffective speedbumps in the face of today’s spam bots and address next to nothing related to trolls. Captchas are more about training inference models (and have you ever correctly picked all the squares with a motorcycle, despite presumably being quite human?), keyword filters are laughably easy to bypass unless they block everything and render the commenting functionality inert themselves, and who on this rock in space would sign up for an account to comment on a random nobody’s photo blog anyway?

Finally, and to loop it back to the incredulity over engagement for engagement’s sake, the push to structure and present all endeavors around the notion that there must be public feedback and metrics to track is no small part of why so much in so many places is so broken. I don’t have a complete and universally persuasive rhetorical framework for the position that it’s okay to simply share things themselves and not always attach public scoreboards, but I do have a disdain for it all. I’m not going to actively build my own engagement metrics-driven prison.

The only idea I might toy with is linking to a companion post on Bluesky that would act as a sanctioned comment thread for blog posts, photos, and whatever else makes it way into the taxonomy of this site. Let them worry about Section 230 and protecting users’ account security. And linking to, rather than embedding, minimizes any cross-site pollution or inadvertant/non-consensual tracking for anyone who might enjoy looking at a photo, but has no interest in telling me.

Regardless, for genuine feedback and conversations, there’s always email: feedback-x-@servernotfound.org.

595 words posted - Permalink

-

A Backlog of Terrific Proportions

For something around the past year, nearly all of my photography and related pursuits have had an audience of one. Aside from quick phone shots to share via stories with primarily friends and family, I simply haven’t had the interest or energy to maintain a real presence on the closed social media platforms. The motivation to do so is really undercut when even close friends and family members who have followed me for years would rarely, if ever, see the photos when I was still posting, because the owners of those platforms would rather fill everyone’s feeds with clickbait and ads.

And so, quick stories when I would land in a new (to me) city or hike up an interesting path or catch a nice sunset were the only public signs of life. For the most part, however, my shutter clicking didn’t slow down. That’s left me in the position of having a couple years’ worth of photos and videos from dozens of countries across four continents that have never seen the light of day outside my devices. Which flies right in the face of why I most love to lug a camera around with me: to share at least a little bit of what I see and experience on this giant rock hurtling through the universe, to maybe, possibly, hopefully encourage someone else to get out and experience just a little bit more during this one precious life we each get.

And so, quick stories when I would land in a new (to me) city or hike up an interesting path or catch a nice sunset were the only public signs of life. For the most part, however, my shutter clicking didn’t slow down. That’s left me in the position of having a couple years’ worth of photos and videos from dozens of countries across four continents that have never seen the light of day outside my devices. Which flies right in the face of why I most love to lug a camera around with me: to share at least a little bit of what I see and experience on this giant rock hurtling through the universe, to maybe, possibly, hopefully encourage someone else to get out and experience just a little bit more during this one precious life we each get.My typical workflow isn’t terribly complex. I start each day out with empty cards in the cameras. In dual slot cameras I always prefer to write duplicates to both rather than use them in series. I’d rather carry a few extra cards and have the redundancy than save the thirty seconds it takes to swap cards, and with card sizes these days I rarely fill them up anyway unless I’m doing video. When I’m done for the day, these cards get emptied out to a set of working folders on paired SSDs, because you can never be too paranoid with duplicates and backups of shots you may never be able to capture again.

These are very roughly organized into a folder structure based on whatever combination of project/trip, date, location, and source I feel is enough to keep my head wrapped around what I’m collecting. I also find it easier to deal with having all the camera shots separate from drone shots separate from action cams separate from field recorders separate from … you get the idea. The SSDs keep receiving each day’s output until they’re full and the next pair of SSDs get handed the relay batons.

This repeats until the trip or project is over, at which point I’m comfortably nestled back in front of my work desk with coffee in hand and a NAS by my side. All the SSDs have their contents moved over to a triage area on the NAS where I can begin the mass grouping and culling. During longer trips, I may have already done light sorting and deleting of obviously-bad shots, but I usually wait until I’m done with that particular photo gathering adventure and have a better sense of what’s going to sit within the margins of usability and may be worth holding on to a bit longer, just in case.

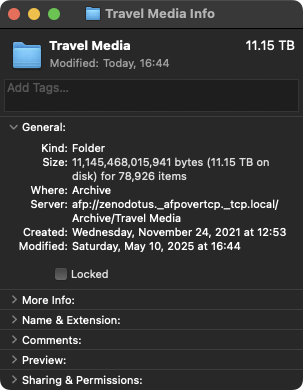

And that’s where I find myself now. I managed to moved some of the really big stuff out to their long-term archival folders, because I generally don’t take a lot of long aerial drone or vehicle-mounted action cam footage and those end up being easier to sort, prune, and archive. But nearly 80,000 photos sit there right now, looming like some impenetrable stone wall between the past few years of travel and my desire to share where I’ve been and some of the things I’ve seen. There’s a method to their current organization, but it is in no way sufficient for the volume of material to sort through in a timely manner.

So forgive me as I slowly sprinkle little bits onto this site. Things will be sparse as I begin to chip away at the massive rock of this backlog.

760 words posted - Permalink

-

Server Not Found

There was a time, long ago, when personal websites thrived. Before a handful of giants muscled their ways to the front, everything that could be was shifted over to walled-off apps, and even search results were replaced with poorly summarized hallucinations that aimed to keep people from venturing too far out again.

Individuals designed and cared for their own unique little corners of the digital landscape, offering up whatever came to mind or caught their fancy on the plots they built and owned. You didn’t have to follow someone in half a dozen separate places to see as much of the world through their eyes as they tried to share. You could stumble across their little garden, and if you enjoyed the things they tended to, you could pop back around whenever you felt like. And from theirs you might even find paths linking to those of friends and common interests.

No need to even know which of the opaque and disconnected industrial silos claimed ownership over a piece of their identity, or to sift through all the inescapable for-you chaff in the hopes you might be able to glimpse a few of their contributions. No need to start over from scratch every time a platform failed, morphed into something unrecognizable or unusable, got caught in a stagnant puddle while the crowd passed it by, or just turned into a nazi bar.

The Apps spent the last decade-plus bulldozing over the open Internet. In its place they offered only engagement-at-any-cost algorithmic swamps of ever-more-bot-filled slop to make the lines on ad revenue charts forever go up and to the right. At least when they weren’t busy being implicated in genocides.

That’s perhaps a bit too dismissive of all the many personal and community sites which have kept their lights on and even thrived. It’s distorted through the lens of my own experience, building and running various sites in starts and fits over more years than I’m about to mention here. Finding myself tempted by the consolidation because of the ease of entry and the excitement, however ultimately toxic, of each like and new follow. But it’s not a unique take and there’s no denying the trend of consolidation onto closed, centralized platforms over the past decade. Platforms owned and operated by entities whose profit motives occasionally aligning with the interests of those who create and share original works is at best a mere coincidence, and one becoming more rare every day as those works are being fed without consent into the sausage grinders of generative slop factories.

I enjoyed the earlier days and am grateful to all those who kept their gardens alive, as well as the handy dandy little tools to manage them, so the rest of us may come back and participate in it again.

Here is my attempt to retill the soil of my old, neglected garden. If you enjoy it, wonderful and welcome! Maybe even consider setting down your own if you haven’t already.

649 words posted - Permalink

Reading List

Entries are not endorsements of every statement made by writers at those sites, just a suggestion that there may be something interesting, informative, humorous, thought-provoking, and/or challenging.

-

Wide-Ranging and General Interest

-

Arts, Media & Culture

-

Politics, Law & News

-

Religion, Philosophy & Ethics

-

Science, Tech & Criticism