Blog

One Does Not Simply Walk Into a Subway Station

Posted

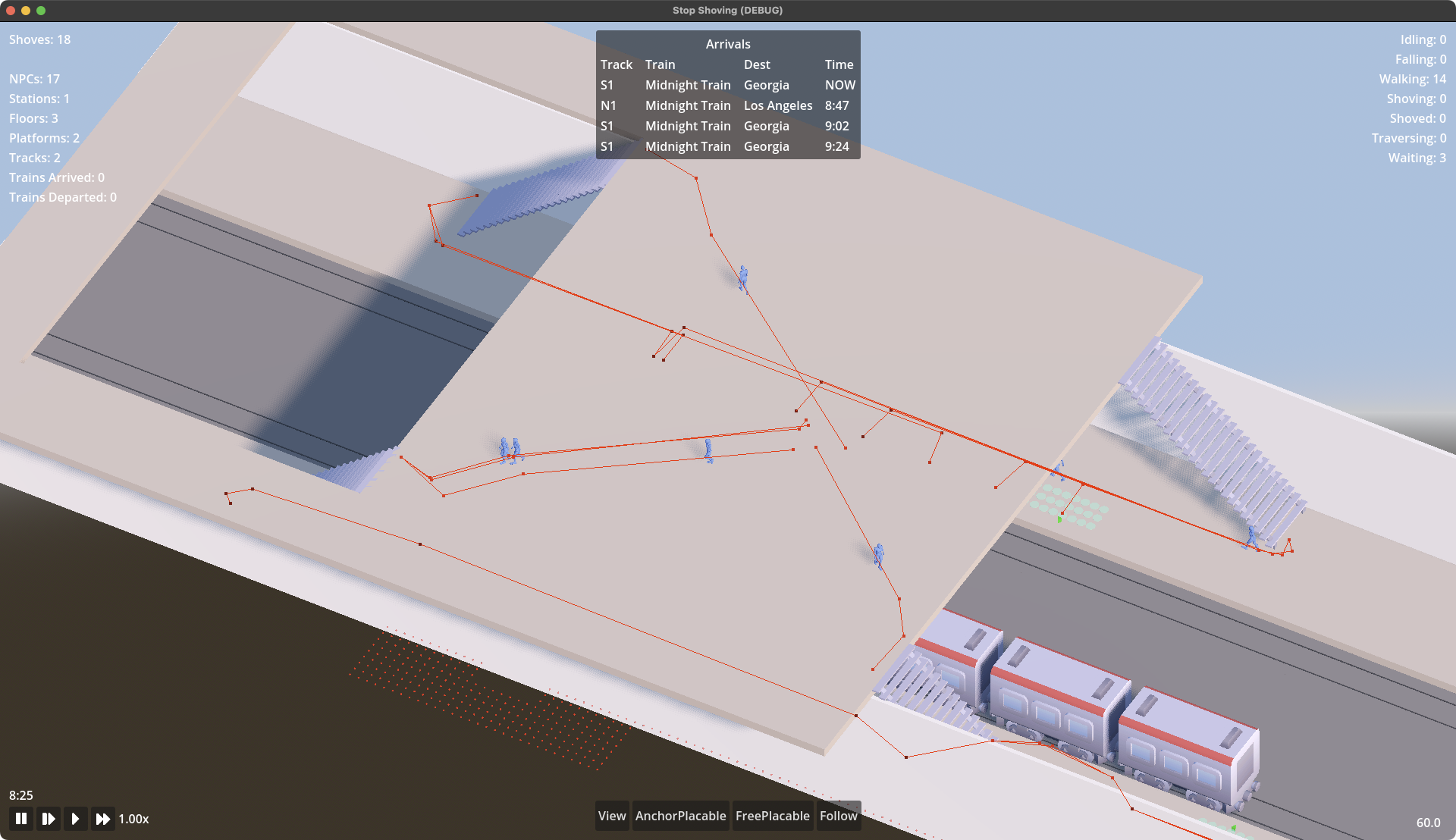

I started greyboxing out some basic station shapes, because at some point I’m going to need to wrangle those Blender shortcuts and what time is better than now to start practicing? As part of moving from the quick and dirty GridMap setup (that was enough to get the first pass on mechanics working) I decided it was also time to tackle the full station routing system (and not just the two-floor-one-staircase placeholder I had slapped together previously).

NPCs don’t spawn at an entrance, or eventually within arriving trains, and just plot a direct course to their final target. A naive system, that might work well in a shooter where you just want enemies to chase down a player, could leverage the NavigationAgent3D system with a NavigationRegion3D covering the entire station. Just keep telling it the Vector3 you want the NPC to reach and let the nav agent blackbox do pretty much everything for you. Set up the mesh and agents well and it’ll work. With one catch: it’ll work every time. The NPCs will get a navigation path that takes them on a reasonably close to optimal walk through the level, and every NPC one after another will follow those same worn paths. Give them the same train to catch and they’ll just be a giant line of ants marching in single file through the station.

The next step up from that is to paint paths through a level, and that’s an incredibly common approach in open world games. NPCs get a bunch of invisible corridors overlaying a map within which they have some room for deviation, but still effectively put those NPCs on rails between various sets of points. The paths can be laid out to look natural if all you do is watch a single NPC follow them. But in the end they’re still tying NPC movement to predetermined routines, and after you see the fifth NPC take the same steps it becomes apparent there’s no actual variation or chaos behind it.

Just as in the real world, the NPCs in Stop Shoving! aren’t going to, nor should they, take the optimal paths. And it’s more than just trying to avoid all the other NPCs moving around. The first time you’ve visited a new city and you’re trying to get from the hotel to a museum, did you enter the subway and know right where to go? Coming home late because you grabbed some drinks with friends, and then realized halfway up the stairs to the street that it was your anniversary and you better have some of the most beautiful flowers in hand or else, and wasn’t there a florist at the other end of the concourse? Or your train’s severely delayed and there’s a restroom one floor up and you may as well since you have plenty of time and a weak bladder. Maybe you just spaced out and walked to the south platform instead of the north.

So NPCs need to be able to move around dynamically, navigate a fluctuating set of Player-induced obstacles, change their minds, and most importantly: get things wrong sometimes. And all in ways that are more realistic than just picking random points in the station and then finding the straightest, shortest line between them. But how can you design a system to get something wrong unless you know what’s right?

The first step is to have a reasonably chunked map of the station that can form discrete areas in which decisions about behavioral changes can be made that are at least somewhat contextualized. NPCs shouldn’t get bored waiting for their train when they haven’t even made it past the turnstiles yet. They probably shouldn’t run back up to the concourse after reaching their target train’s platform just so they can go on a pastry shopping spree (wouldn’t blame them, though). Given that, stations need to be sectioned off into platforms and floors, and floors need various types of conveyances to connect them - stairs, elevators, and so on - and all of it together ends up forming a strongly-connected, directed cyclic graph. The floors are nodes, the connectors (stairs, etc.) are the edges, and in real-world stations there is always at least one path from each node to any other, even if it would require the NPC to retrace their steps back to a starting position out on the sidewalk.[1]

I’m fortunate there’s already deeply researched ways to figure out what paths exist in all sorts of graphs. Most commonly they’re used to find shortest or optimal paths, and in fact the built-in navigation support in Godot (and most game engines) relies on modified Dijkstra’s and/or A* algorithms. Almost all of them are focused on shortest paths or just sheer computational efficiency, but we can start with a recursive DFS algorithm, toss in cycle checks, calculate weights as we go, and get something that serves this game’s “give me as many paths as possible and make some of them slow and inefficient!” needs. It’s a variation of Tarjan’s strongly-connected components algorithm, but rather than detecting all strongly-connected subcomponent graphs its aim is to discover all non-cycling components between two arbitrary nodes. This algorithm, in a way, is returning a collection of halves of what Tarjan’s does, because we don’t need to get back to our starting point each time, we just need to make it to any arbitrary mid-point.

The approach now is pretty straightforward, and it’s completely automated as long as I put the Area3Ds in the correct spots to register floor/stair/elevator/track connections[2]. Upon level loading, the station collects all these area designators based on their collisions, and can build a dictionary of adjacencies such that every single floor and conveyance has an entry in the dict, and their corresponding values are an array of every outbound connection. Outbound only as this is a directed graph, since things like escalators (an edge between two floor nodes) only move in a single direction. Because it’s based on automatically scanning for overlapping areas, there’s no special configuration for any level and the routes generator doesn’t care if the station has one floor or a hundred[3]. It just gets a bunch of adjacencies in a data structure that looks like this if created directly instead of constructed dynamically from colliders and areas (full object references trimmed down/out for readability):

var adjacencies : Dictionary[Node3D,Array] = {

"floor1:<SSG_Floor@23...>": ["southstairs1","southstairs2","northstairs1","northstairs2"],

"floor2": ["southstairs1","southstairs2"],

"floor3": ["northstairs1","northstairs2"],

"southstairs1": ["floor1","floor2"],

"southstairs2": ["floor1","floor2"],

"northstairs1": ["floor1","floor3"],

"northstairs2": ["floor1","floor3"]

}

Or if you’re a visual learner, that adjacency mapping is what this test station looks like as a cyclic graph. It’s directed, too, but since I’ve only implemented stairs, which are two-way, you can’t really tell in that data structure. Once I have working escalators, you would be able to infer the directed nature of the graph by non-paired edges. That first entry in the dict indicates that the floor1 object (an SSG_Floor, but the dictionary keys are typed to Node3D because they can be either an SSG_Floor or an SSG_FloorConnector (or rather, one of the conveyance-specific subclasses of it) and those classes only share a common root at Node3D) has four outbound edges: southstairs1, southstairs2, northstairs1, and northstairs2. It says nothing about where those edges lead. That’s where the graph traversal comes in. The recursive, depth-first traversal function can descend into each of those edges, and repeat that process until it finds its destination at which point it has a fully constructed path that can be added to the cache.

But how does it know its destination (or its origin for that matter)? A separate data structure was built just outside the route generator:

var routes : Dictionary[SSG_Floor,Dictionary] = {}

for from_floor : SSG_Floor in station.floors():

routes[from_floor] = {}

for to_floor : SSG_Floor in station.floors():

if to_floor != from_floor:

routes[from_floor][to_floor] = SSG_RouteSearch.get_routes(from_floor, to_floor)You might cringe at first at the nested loop building a dictionary of dictionaries that is the square of the floors present in the station. But two things should quell that misplaced revulsion:

-

How many subway stations can you count that have more than a couple dozen floors, or even half a dozen?[4]

-

This is a one-time generation and memory cost for the sake of super fast simultaneous lookups by an arbitrary number of NPCs, when those lookups need to happen during the time-sensitive physics process of the simulation.

This will spend, at worst case, maybe a few hundred milliseconds at level load and a megabyte or so of memory to give single digit microsecond route lookups even in a station with dozens of floors and more elevators than you can shake a counterweight at.[5]

So now that we have our station represented as a directed cyclic graph encoded into an adjacencies map (which, remember, required no special setup other than the meshes for floors and stairs having the appropriate Class assigned to them - easy-peasy!) and we have the list of every pair of floors that exists, we can start to call that route generator (which is actually done in the very last line of the code above at the innermost part of the nested loop). That recursive DFS is as simple as this:

static func get_routes(from_floor : SSG_Floor, to_floor : SSG_Floor) -> Array:

if from_floor == to_floor:

return []

if not (Adjacencies.has(from_floor) and Adjacencies.has(to_floor)):

return []

var routes : Array = []

for adjacency in Adjacencies[from_floor]:

get_next_step(routes, [from_floor], adjacency, to_floor)

return weighted_routes(routes)

static func get_next_step(routes : Array, traversed : Array, next : Node3D, dest : Node3D) -> void:

if next == dest:

traversed.push_back(next)

routes.push_back(traversed)

elif Adjacencies.has(next) and not traversed.has(next):

traversed.push_back(next)

for adjacency in Adjacencies[next]:

get_next_step(routes, traversed.duplicate(), adjacency, dest)There isn’t really anything impressive happening in there. But there are a couple important things to note. The first is the cycle checking, which is handled in the traversed array that gets passed into each recursive call. It also functions as our constructed path, a copy of which gets pushed onto the end of all the discovered routes every time the destination floor is reached. If things got really bad, we could even use it as a way to limit recursion depth with a quick short-circuit when traversed.size() > MAX_RECURSION.

Any adjacency which is not the destination floor gets a quick check that we know about it (just a little extra paranoia that really only covers the case of a broken station layout) and that we haven’t seen it before. That’s the actual cycle check. If it passes those tests, then hooray, we’ve stumbled upon an undiscovered path! It’s added to the traversed array, and now all we have to do is get all the adjacencies of that entity in the graph and repeat the entire process over. Note that every single call into the recursive get_next_step(...) function receives a copy of the traversed array, not the original. This is critical for the back-tracking piece of the DFS algorithm, otherwise we’d have this one endlessly-growing (and very much invalid) path at the end of all this. Each level down in the recursion starts off with the last graph component before the recursion before it.

In the end, every non-cycling path between every single floor pair in the station will have been discovered and cached for lookups later. All an NPC needs to know is what floor they’re on and what floor they want (or think they want) to be on, and one nested dictionary lookup later they have an Array containing every way to get there, which looks like this:

{

"floor2": {

"floor3": [

{ "route": [ "southstairs1", "floor1", "northstairs1", "floor3" ],

"cost": 48.6 },

{ "route": [ "southstairs1", "floor1", "northstairs2", "floor3" ],

"cost": 28.0 },

{ "route": [ "southstairs1", "floor1", "northstairs2", "floor3" ],

"cost": 28.0 },

{ "route": [ "southstairs2", "floor1", "northstairs2", "floor3" ],

"cost": 48.6 }

]

}

}That snippet shows just the portion for paths originating from floor2 and ending at floor3, but the fully constructed routes cache includes similar entries for all floor pairs. Once the NPC decides which of the routes to use, they’ve got a handy-dandy pop()-able array of navigation targets. My next target is a floor connector so query it for an ingress point that’s located on my current floor.[6] And now the NPC knows where to walk in the sub-region of the station in which they’re currently located.

Final note, since I’ve definitely rambled on too long already: what’s that cost entry? That’s how NPCs can rank the paths. It’s a sum of all the weights for every edge and node in the route. In a shortest-path graph traversal algorithm like Dijkstra’s you’d get a single path back that would have been one of those with the cost of 28.0. But a thousand years ago near the beginning of this post, I laid out a requirement for this route generator: the NPC navigation system needs to know about multiple paths, including the bad ones.

The weights that go into that final cost include things like the distance an NPC would need to walk (in the example route data above) along floor1 to get from the southstairs1 to the northstairs2 as well as the relative movement cost of using whatever conveyance connects different floors. Stairs are more cumbersome to use, so the same distance in meters on stairs costs more than walking along a flat floor. Riding an escalator costs less than walking. Elevators have costs based on not just the distanced traveled, but how many floors they might need to stop at along the way (or stop at before they can even pick up the waiting NPC).

Thus, an NPC with high perception or one which finds itself surrounded by navigation hints in the station will have a much higher chance of selecting a route that is cheaper. NPCs suffering from confusion have an increased risk of selecting a more costly route. I’ve left the actual calculation of those costs out of the code above because it’s highly specific to this game’s simulation, and would be a distraction to the route generation rambling here. It’s also still undergoing tuning.

There’s one more thing with the routes generator[7] I haven’t implemented yet, and will probably wait until I build more conveyance types, which is accessibility flags. An NPC in a wheelchair or dragging a 40kg suitcase is going to want a way to filter out routes that use stairs and strongly favor ones that only have elevators, ramps, and maybe escalators. That will probably take the shape of a bitmask that sits within the route dict, alongside the route and cost entries, but for now that feature is just a backlog item in Jira.[8]

Anyway, I hope that all was interesting. It probably wasn’t. You have my deepest concerns and sympathies if you made it all the way through. This has served its only real purpose, though, which is that I think better when I try to write it all down.[9] I fixed a couple minor bugs and made one performance improvement just in the course of these more than 3,000 words.

I suppose a station could physically have a floor only reachable by a one-way escalator with no egress conveyance, but no public mass transit system is going to be able to violate their locality’s fire and safety codes like that. ↩︎

I think I’m going to make that a whole separate blog post later, because this one is running way too long already. ↩︎

Eventually it will care, but this setup is done once per level and then cached for speed during gameplay. On my main development machine (a 2013 M2 Max Macbook Pro that has Godot, Blender, VSCode, Photoshop, Bridge, and a thousand Firefox tabs all running simultaneously) it runs in milliseconds even in larger station structure tests. ↩︎

I have a little note tucked in the back of my game design doc that the two Final Boss stations will probably be Seoul Station from Seoul, South Korea and Shinjuku Station in Tokyo, Japan. I did get pretty good navigating around a solid chunk of the nearly 800 stations within the Seoul Metro over the course of the nearly six months I stayed there in 2024 and early 2025. Shinjuku Station, however, defeated me every time. I’m going to chalk up my countless humiliations there over the past couple years to the ridiculous amount of construction they have going on. ↩︎

In this sample station, which is admittedly very small, the entire route generation process takes under 100μs. But yes, the math nerds reading this will scream, “Recursive DFS doesn’t run in constant time!” and that is absolutely true, but I’ve mocked some dummy stations with plenty more floors and connectors and for real-world station layouts we’re still talking sub-millisecond to double-digit milliseconds in extremis. And the nested dictionary lookups take under 2μs each time an NPC needs to pick a route from the cache. ↩︎

Or for rude NPCs, they can query for an egress point that also allows ingress - in other words, walking down the culturally-inappropriate side of the staircase and thus getting in the way of NPCs with higher social cohesion. I’ll probably go more into that in a later blog post about how floors and conveyances are constructed inside levels. ↩︎

Final-final8_Done_blogpost-lastrevision-1(Ready_to_publish)-Reviewed.md ↩︎

Gods save me, but yes, I’m using Jira on a solo dev project. Don’t ever let anyone accuse me of practicing self-care. ↩︎

Not that anyone would ever be able to tell from the poor quality of the writing. ↩︎

Reading List

Entries are not endorsements of every statement made by writers at those sites, just a suggestion that there may be something interesting, informative, humorous, thought-provoking, and/or challenging.

-

Wide-Ranging and General Interest

-

Arts, Media & Culture

-

Politics, Law & News

-

Religion, Philosophy & Ethics

-

Science, Tech & Criticism