Blog

The Sidewalk Salsa and Cultural Sensitivities

Posted

Walking along a city sidewalk or heading down a narrow hallway, not one of us has avoided doing that little dance at least once. Living in large cities, and even occasionally leaving my apartment for a few minutes each week, I’ve done the Sidewalk Salsa a thousand times.

You twist to the right, but they mirror you. You twist back even further to the left, and they’ve already tried to correct their ill move. Or perhaps you’re the inadvertent aggressor in this ambulation incursion. Now you’re both locked in a battle of wills, ego, and agility of the hip flexors to see who forces a weak laugh first and, stopped in place with palms turned up, yields the entire avenue through a gentle swing of their arms and a slight nod of the head. Or perhaps one side believes defusing the tension and mutual embarrassment requires play as a linebacker[1], only prolonging the interruption of travel for everyone involved.

Or so it frequently happens when the crowds are thin and at least one party isn’t racing to their destination. When time is short, and moods moreso, the salsa can quickly become a skirmish. Mettle replaced by brute physicality, and then the shoving begins. But most people aren’t seeking out conflict, and thus ends the intro to this post.[2]

How to capture these kinds of interactions in a crowd simulation within the confined spaces of mass transit stations? How to get two or more NPCs on a collision course to try to avoid each other, but do it awkwardly and leave open the chance that one of those NPCs is just a big ol’ jerk? Most importantly, how to do it all while respecting cultural norms around the world?

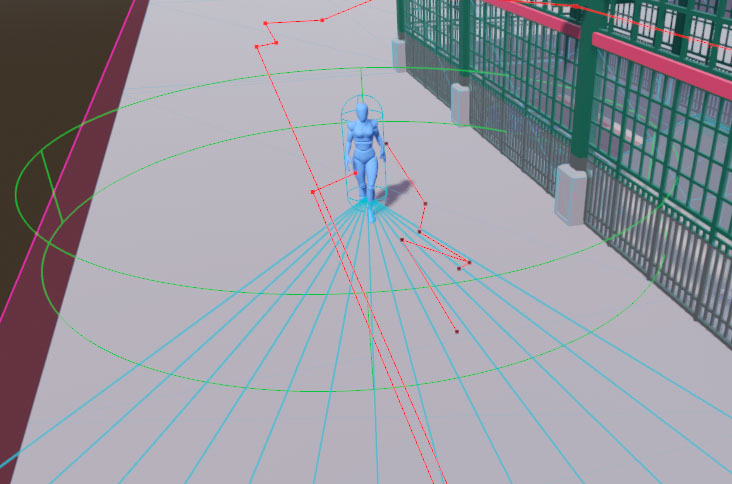

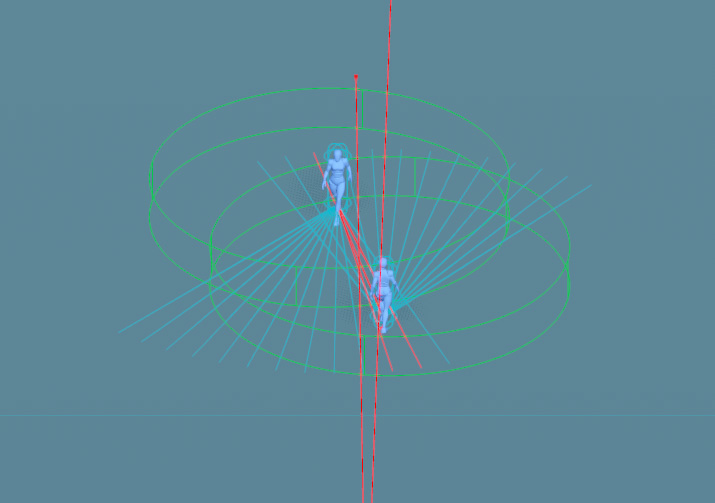

The core of Stop Shoving!'s approach[3] begins with an arc of RayCast3Ds projected in front of every navigating NPC. Each has its origin at the same point just very slightly in front of the NPC and their rotations are made at even intervals such that their target points form an arc some distance ahead of the NPC. This configuration can be trivially tailored to each NPC to give more individualized behaviors (more situationally aware NPCs can have a larger arc, more myopic NPCs a narrower one; more nimble NPCs can have more rays, less agile and responsive NPCs fewer) using just a few variables:

@export var num_rays : int = 13:

set(n): num_rays = clamp(n + (n % 2) - 1, 3, 21)

@export var ray_arc : float = 60

@export var ray_len : float = 7.5

@export var ray_cluster_margin : int = 2We’ll come back to the ray_cluster_margin in a bit. Aside from explaining that ray_arc is the total rotation (in degrees, not radians) to be made from the right-most ray to the left-most ray, and that ray_len is the length of each ray (in meters), the first important thing to point out is that the number of rays each NPC uses must be odd, as we will always want one ray to act as the dead-ahead center ray in this scheme. The custom setter on the num_rays variable ensures this,[4] as it also ensures that there will always be at least 3 rays and no more than 21.

The maximum number is arbitrary and is there to prevent an NPC from bringing down armageddon on the physics thread. The defaults in this snippet are what I’ve been using most recently for testing the simulation, but they’re by no means some set of magic numbers that has perfectly captured real world human behavior. They do a pretty good job for the purposes of the game as-it-is so far, though.

With those values set, it’s possible to construct an array of rays, fanning out from the NPC. With a few pieces removed for brevity, it looks like this:

var arc_start : float = (ray_arc / 2) * -1

var arc_incr : float = ray_arc / (num_rays - 1)

var rays : Array[RayCast3D] = []

for i : int in num_rays:

var ray_rot : float = arc_start + (arc_incr * i)

var ray = RayCast3D.new()

ray.target_position = Vector3(0,0,ray_len)

ray.rotate(Vector3.UP, deg_to_rad(ray_rot))

rays.push_back(ray)The full implementation adds each ray to a Node3D underneath the NPC’s root so that it’s active within the physics engine, and for convenience it’s that node which is offset just a smidge in front of the NPC so the individual rays don’t need to worry about it. I’ve cut that out so this example focuses just on getting the rays created and pointed to the correct spots. Also, if you want to build a similar setup in an engine other than Godot, take care to remember that while Godot uses a Y-up-right-handed 3D space, not all engines do. A Z-up engine would require adjusting the vector assignment for the length to use the correct X or Y axis depending on your NPC orientation, and a left-handed engine would require arc_start = (ray_arc / 2) as well as ray_rot = arc_start + (arc_incr * i * -1) to have everything else in this post work as intended.

This gives us an array of rays where (n-1)/2 will fan left from the NPC’s forward position and the other (n-1)/2 fan out to the right, and a single ray will stick out directly in front with no rotation at all. A larger num_rays packs them in tighter for more fine-grained detection and avoidance, and a higher ray_arc allows the NPC to consider a larger area when trying to avoid another NPC.

How do we use this array of rays, then, to have NPCs move around each other? Glad you asked, maybe I’ll write up a blog post on it! In the meantime, here’s how we use them: a combination of clusters and biases. Good biases, not the nasty, evil, all too pervasive ones that cause us to not love one another as sisters and brothers.

In some countries, everyone drives on the right, others the left. (In a few it’s both, depending on the region and its colonial history.) In most, walking patterns match. Oblivious tourists shoulder-checking locals, not just because it may be crowded, but because they aren’t picking up on the cue that nearly everyone around them is walking and yielding to the left while they barrel their way down the sidewalk on the right like they do back home. We can encode this in a regional setting that station scenes use: a bias which is going to give us an easy way to enforce[5] this right vs. left handedness in societal and cultural norms, and oh-so-conveniently it will also give us a way to get NPCs to do those awkward little dances.

func get_directional_bias() -> int:I’m going to be real hand-wavy about this part, because what that SSG_NPC instance method does internally is very specific to how Stop Shoving! works; checking for the station’s regional setting, potentially modifying it for the NPC’s attributes around social cohesion, confusion, and so on. The only important part is that the method ultimately returns an integer, either -1 (to signify right) or 1 (to signify left), and nothing else. This method is also only called infrequently and it only produces a new and potentially different value at various frame intervals (i.e. you could call it repeatedly in the same frame and you’ll get back the same result, but call it again, say 12 frames, later and it might change its mind). It isn’t something that’s queried throughout the collision checks, but rather a one time pre-avoidance-routine setup call. With that all poorly explained, tuck the notion of the bias away for a moment.

Earlier I promised we’d get to that ray_cluster_margin export variable, and now that now isn’t earlier, let’s consider doing so. We built an array of rays above, but when checking for impending collisions (and looking for places to nudge the NPC where there won’t be any) we aren’t going to consider just one at a time. If an NPC is about to run into something, we need to find a direction they can turn to which has a high likelihood of not encountering something else to hit.

A RayCast3D is, despite its name, actually a one-dimensional construct; it’s just one that you can use inside a 3D space (as opposed to the RayCast2D which is also a one-dimensional construct, but one that works in 2D space). It is a single point projected along a single axis, and thus can only detect a collision in a very small area; much smaller than an NPC. This feature makes them very cheap (relatively speaking) to use but can easily lead to a scenario where the ray just happens to find a sliver of space right in between two other objects that narrowly misses them both for a point in space, but produces an angle from the NPC which would still cause collisions for the character’s body.

There are other ways of checking for collisions in Godot, as in any other engine. We could use an array of neighboring or overlapping Area3Ds, each a pizza slice of the semi-circle ahead of the NPC. That would give us effectively perfect detection of non-colliding areas the NPC could turn towards if the one in front of them has any NPCs. But we’d need several, and Area3Ds, especially non-primitive (cube, sphere, cylinder) shapes, are very expensive. We’d hit the physics engine’s limits quickly and our stations would only be able to contain a few dozen NPCs or less before the framerate collapses.

We could try to optimize physics performance by only persisting the center one during navigation and dynamically creating the others only as-needed, but then we just move a lot of load over to the main thread and we introduce latency in between detecting a forward collision and being able to start scanning for non-colliding alternatives. The collision detection on each of the new areas dynamically generated wouldn’t be available until at least the frame after the one in which they were added.

Another option would be to use ShapeCast3D. These are similar in concept to the RayCast3D in that you have an origin point and a target, and anything between the two will collide. The difference is that the ray cast projects a single point along that axis, whereas the shape cast moves an entire and arbitrary CollisionShape3D along it which can be used to cover whatever size area you desire. As with using Area3Ds, this is substantially more compute intensive than a raycast, but it can be implemented more efficiently than a series of fixed areas and in a way that reduces latency if performing the shapecast sweep directly against the physics server.

In a simulation that either has a defined upper limit of NPCs to consider[6] or doesn’t need to maintain high framerates in realtime, shapecasting would be my preferred solution. One shapecast per NPC persists at all times while the NPC navigates, projected forward, with a lateral dimension equivalent to the NPC’s collision size. Upon registering a collision, the point of that collision in global space could be used to then shapecast almost-perpendicularly in the direction of the bias until a segment large enough to accommodate the original NPC is found. That area then defines the new safe trajectory of the NPC. Repeat those checks ad nauseum while the NPC is moving about and until you sprinkle in a little human-like variance, you’ve got a nearly perfect little avoidance system.

But that’s all still very expensive as you start piling on the NPCs. So performance constraints demand that we work with the humble raycasts, which is fine because video games are nothing if not smoke and mirrors. It just has to be good enough while remaining fast.

To compromise, we’ll bundle up those raycasts into overlapping clusters, and set a rule that if any one ray in a given cluster is colliding then we treat that entire cluster as colliding. This is going to let us fake more than one dimension of coverage. And for the third time I will call out ray_cluster_margin and this time I’ll actually explain what it is: the number of rays to each side of whatever ray we’re currently dealing with that will be considered members of the cluster. A margin of 1 means the clusters will be 3 rays (the current ray, plus one to each side). Just as with the entire set of rays, the clusters will always have an odd number of rays within them so that we have, at all times, a center ray to deal with.

It’s been a while since some code, so let’s see what the cluster-based ray scanning looks like with all the above in mind. I’m going to break the scanning method up into three parts, beginning with this first chunk:

func get_avoidance_vector() -> Vector2:

var ctr_ray_i : int = int(rays.size() / 2.0)

var ctr_ray : RayCast3D = rays[ctr_ray_i]

var cluster_colliding : bool = false

var bound_low : int = 0

var bound_high : rays.size() - 1

var first_ray : int = clamp(ctr_ray_i - ray_cluster_margin, bound_low, bound_high)

var last_ray : int = clamp(ctr_ray_i + ray_cluster_margin, bound_low, bound_high)

for i in range(first_ray, last_ray + 1):

if rays[i].is_colliding():

cluster_colliding = true

break

if not cluster_colliding:

return Vector2(0,0)In this instance method, which returns a Vector2, we do the ray scanning. This vector will ultimately have two things, although for this post we really only care about the first: an angle (in radians along Vector3.UP) the NPC should pivot towards to avoid a detected collision. The second part is a speed adjustment, though I’ve removed the code from these examples that calculates that as it’s not germane to the heart of this writeup. In short, if you’re curious: it will cause the NPC to slow down if every option will lead to a collision (in order for the NPC to buy more time for better options to emerge as others move around them), or it will speed them up when the way ahead is clear.

It starts out by getting the middle index of the array (the explicit cast doesn’t produce anything different from just doing rays.size() / 2 aside from suppress a debugger warning about the loss of precision from integer division), grabbing a reference to the center ray, and initializing a colliding flag. And it also sets the upper and lower boundaries of the rays array, just so we don’t have to keep repeating the call to rays.size() a bunch elsewhere.

The method moves on to special-casing the center cluster of rays[7] to see if we even need to worry about avoiding something. Remember earlier that any individual ray in a cluster colliding means the cluster collides, so as soon as we find one that’s hitting another NPC, we set the flag to true and break the loop. There’s no point wasting anymore cycles checking the rest of the rays. One rotten ray spoils the whole bunch.

If there was no collision, the method immediately returns a 0 adjustment angle which allows the NPC to continue moving along their originally intended path with no changes. You may note the first_ray and last_ray variables, which are easy enough to correctly guess that they define the range of rays in the array to consider for this cluster (ctr_ray_i minus and plus the margin). These values must be clamped appropriately to avoid any out-of-bounds errors on the array access, in case the margin exceeds the size of the array. For example, setting num_rays = 3 and ray_cluster_margin = 5 would lead this method to try to access elements -4 .. 6 of a 3 element array. Straight to jail! Clamping these two ray index values to the actual boundaries of the array eliminates this problem. The clamping also plays an important role even when the ray count and margin are set properly. More on that in a second.

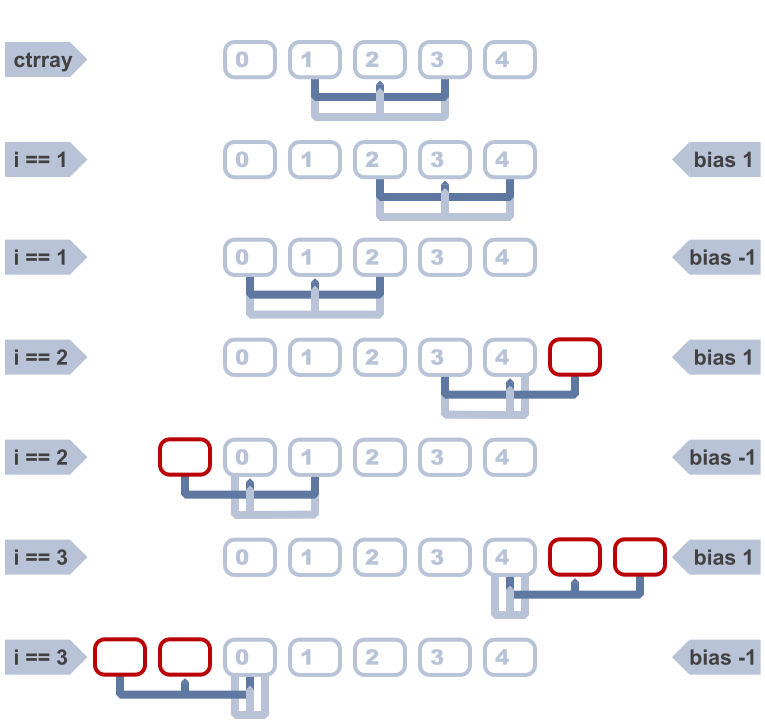

The next part of the method does something that seems really incredibly dumb at first, just hammering away at batteries levels of stupidity. It takes half the size of the rays array plus the cluster margin (plus one, because range() loops stop before the final value), makes a range of integers from that, duplicates them, and stores it all in a new array. That seems at best odd, at worst believes in chemtrails scales of idiocy. Except that it’s integral to taking the bias from fifteen chapters ago and using that to dance the salsa, to do a little cha-cha. This can be (and in my full implementation is) done once, whenever the rays array is created or modified, rather than during each avoidance check. But it makes a lot more sense to show it here since the entire reason for it is using it with the bias and the code is the same either way[8].

var indices : Array = []

for i : int in range(1, int(rays.size() / 2.0) + ray_cluster_margin + 1):

indices.push_back(i)

indices.push_back(i)If the NPC has 5 rays and a cluster margin of 1, then the indices array above will end up being [1, 1, 2, 2, 3, 3]. 0 is skipped because we already special-cased the center cluster and it would be a waste to check it again. (Wait, index 0 is the center ray? you ask. Hold your horses, we’re about to get to that.) Why on earth would we want this? Let’s look at how the non-center ray scanning works now:

var bias : int = get_directional_bias()

for i : int in indices:

var cur_ray_i : int = ctr_ray_i + (i * bias)

first_ray = clamp(cur_ray_i - ray_cluster_margin, bound_low, bound_high)

last_ray = clamp(cur_ray_i + ray_cluster_margin, bound_low, bound_high)

cur_ray_i = clamp(cur_ray_i, bound_low, bound_high)

bias *= -1

cluster_colliding = false

var cluster_vector : Vector2 = Vector2(rays[cur_ray_i].rotation.y, 1.0)

for j : int in range(first_ray, last_ray + 1):

var cur_ray : RayCast3D = rays[j]

if cur_ray.is_colliding():

cluster_colliding = true

break

if not cluster_colliding:

return cluster_vectorAlmost right away, that funky doubled-up half-the-rays array is what we’re looping over. But that doesn’t mean we only check half the rays, nor are we checking any cluster twice. First we call our buddy from earlier, the get_directional_bias() method. We call this once before starting our loop across the clusters. Except we’re supposed to be dancing left and right, not just one direction? That’s why we needed the index offsets twice. Offsets being key. Each one of the values in indices is an offset from the center of the entire rays array, and with each loop of this check we apply our bias, then we flip that bias for the next loop iteration. So if the NPC’s first inclination is to swerve right to avoid a collision because they’re in North America, but they still collide, then they’re going to bias *= -1 and swerve left. Except the second iteration of this loop is still going to have an i == 1 like the first one, so the NPC will check the cluster beginning just one index offset from the center ray again only in the opposite direction. It won’t be until the third iteration (another bias *= -1 to swerve back to the right) that i == 2 and the ray scanning will move one more offset outward from the very center.

Salsa achieved!

Something you may have noticed is that a 5 element array is going to have an index range of 0 .. 4 with a center index of 2. But our offsets list goes up to 3 and 2 + 3 == 5 and even though a certain country abolished its Education Department, the inescapable fact that five is greater than four still applies even to computers there whether the humans believe it or not. Similar to the clamping earlier, the first_ray and last_ray clamps in this loop ensure an out of bounds error doesn’t occur. So why even have the extra numbers (recall that it’s not just one extra offset, it’s ray_cluster_margin offsets)?

If you’re a visual learner, the following diagram (click to embiggen) shows the progression of the cluster scans assuming an arc composed of 5 rays with a cluster margin of 1. The darker lines show the pre-clamping index ranges at each cluster, while the lighter lines show the post-clamping range. The arrow-ended line inside the range represents cur_ray_i in the code snippets above. Red boxes denote the out of bounds indices which clamping prevents. A five ray arc is pretty small, and testing stations yielded pretty poor avoidance results. I’ve generally found 11-13 to be a good compromise so far, depending on the size of the arc, but then this diagram would take up too much space before it got to the good part of showing the narrowing search at the ends of the arc.

At the extremities of the ray arc, if everything has been colliding and the NPC is getting desperate for a way out, smaller clusters that don’t collide are better than nothing. So the offsets go beyond the boundary of the array by the size of the margin, which means we can check successively smaller clusters at the edges of the array all the way down to a single ray.

This is also why we add a clamp on cur_ray_i itself (but only after calculating and clamping the first and last ray index values), because as the clusters extend off the edge of the array, we have to treat the very first/last ray in the array as the current one.

With all these bounds and ranges set up, we can do the same thing we did with the center cluster. Look at the rays and the first one that’s colliding short-circuits the cluster check and breaks the inner loop. The last bit of the current cluster scan is to either return the angle of the center ray if the cluster is unobstructed, or to move on to the next cluster. Then, if all else fails and we’ve exhausted all of the offsets without a non-colliding cluster, there’s a little bit not shown here that returns the 0 angle vector with a speed dampener.

There’s a few improvements that could still be made. One possible optimization is to memoize or locally cache the is_colliding() return value so we don’t need to call the method itself multiple times for the same ray when it appears across different clusters. The gains there would be minimal, though, since the collision detection itself was already performed in the physics engine and the method is just returning the result. There’s no extra physics work being performed each time, since we aren’t calling force_raycast_update() after modifying a raycast inside the same frame.

But that hints at another optimization we could investigate: instead of instancing all the separate RayCast3D nodes and letting them run continuously, we could instance only the center cluster’s worth of rays (as those get checked every frame currently, regardless, to know whether to engage the actual avoidance procedure). As long as they aren’t colliding, that’s the end of the story for that frame. And when there’s more NPCs in the scene that aren’t on a collision course than are, the savings in nodes could be worth it. However, as soon as that center cluster does collide, the remainder of the method shown above could sweep one ray around to each position, force a raycast update, check and cache the collision value, and do so until a non-colliding set of angles that make up one of the clusters is found. Reset the ray to its original position (for the next frame) and send the avoidance angle back.

Assuming the overhead of raycast update forcing is minimal, that could be a performance win by limiting the number of raycast collision detections per frame to the actual minimum necessary to keep NPCs moving freely. Something for the backlog, since the current method has been plenty performant in testing so far. I’ve got much bigger fish to fry from the flame graph than that right now.

Another optimization that I haven’t implemented yet, but plan on adding, is skipping avoidance checks on various frame intervals. I have a similar optimization on other sometimes-expensive systems in the simulator already and done with the right finesse in choosing intervals, the performance benefits are pretty noticeable. The idea is simple: count down every frame from a desired interval value and once you hit zero, do the thing, reset the counter and repeat. You only do the expensive calculation every N frames, and because NPCs aren’t spawning on a global interval boundary (i.e. they spawn whenever they spawn, not strictly at ticks_msec % 1000 == 0 or some nonsense like that) their counters will tend toward a natural jitter, thus evening out the load on the engine without any additional trickery.

The catch is figuring out what you can safely do on intervals like that, and how large those intervals can be before the system breaks down. Having NPCs only perform their avoidance checks every 5 seconds would vastly reduce the computational cost of the system, but it would also render it useless. Having them check every other frame might sound like it makes it half as costly, but then you have the slight overhead and the added indirection of the counters. But NPCs could probably get away with only checking for avoidance adjustments once every 5-10 frames until they start detecting collisions, and then ramp it up to recheck more frequently until the coast is clear again. Is the savings from doing one fifth to tenth the calls to get_avoidance_vector() (but still having the arc of rays persistent) enough? Seems reasonable to assume it will be, but only some profiling will tell.

So, that’s the basic Sidewalk Salsa avoidance system between NPCs in about five hundred nutshells. As always, if you read through my entire incoherent rambling, I’m both impressed and a little bit terrified! If you’d like to see more, if these table-breaking treatises are interesting or provide any value to you, I’d love to hear about it. Contact info is on the About page. And if you somehow find enough value in these screeds to unlock a bit of generosity, I’ll never turn away a little support.

Don’t come at me for possibly choosing the least apt position for this example. I know next to nothing about the game beyond it involving Very Big Guys running into each other so they can get the Most Brain Injuries trophy. ↩︎

Segue schmegway. ↩︎

Being developed in Godot, the examples here will use nodes and language features of the same, but almost everything here has a direct or very similar counterpart in other engines. ↩︎

But make sure you choose a default that is odd, as the custom setter won’t intercept and fix that; only subsequent assignments. ↩︎

Mostly. As always, rude or misbehaving NPCs can flout the defaults by inverting their behavior under the right conditions. ↩︎

Where that limit is higher than what a bunch of persistent

Area3Ds can handle but low enough that shapecasting remains performant. Perhaps we’re building something that just needs modest numbers of NPCs at a time navigating hallways, where we also want to make sure we only detect things on the same side of the walls as the NPC. This still wouldn’t work for hundreds or more in an expansive transit concourse. ↩︎Sidebar: At least half the bugs I end up catching in my code are me forgetting that

range()produces a list that includes the start but excludes the end. I should submit a PR to Godot that adds arange_that_does_what_you_thought()method. Case in point, theforloop in that snippet left out the required+ 1until I was editing this post. ↩︎Just make sure

indicesis accessible by both methods by making it an instance property instead of a method local variable. ↩︎

Reading List

Entries are not endorsements of every statement made by writers at those sites, just a suggestion that there may be something interesting, informative, humorous, thought-provoking, and/or challenging.

-

Wide-Ranging and General Interest

-

Arts, Media & Culture

-

Politics, Law & News

-

Religion, Philosophy & Ethics

-

Science, Tech & Criticism